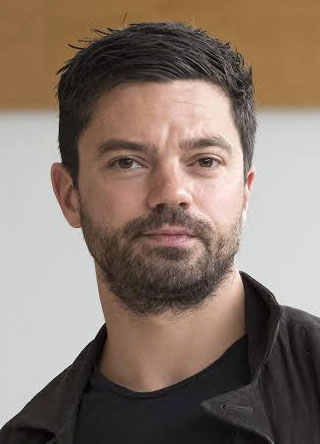

Dominic Cooper established his name with THE HISTORY BOYS more than twelve years ago. Since then he has often played rotters and his latest role as John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester in THE LIBERTINE which opens at the Theatre Royal in Bath on 31st August does nothing to dispel that image. Here he talks about the play and his part in it . . .

What attracted you to The Libertine?

Someone mentioned the play to me – I think it was an actor who wanted to direct it – about two years ago, maybe more. I got approached about doing it but it never happened at the time, but I read it and loved it. Then very strangely my agent said to me ‘Do you fancy doing a play?’ and I said ‘Yeah, I’m desperate to do one’. She said ‘What play do you want to do?’ and when I said The Libertine she said ‘Are you joking? I’ve just put down the phone from the producers who are looking for someone for The Libertine’. That’s absolutely how it happened. From the moment I first read it I loved its wit and its humour and the world of excess and the lifestyle he led at that time in England. It was a huge time of change and I was interested in how Rochester felt towards the King; what close proximity he had to the King and how he treated him. He’s such a complex, confused, dark man who never really fulfilled his potential. He was his own worst enemy in that his intellect caused complications; it hindered him more than it helped. There are so many layers to him and it’s a part that hopefully I will do justice to. I’m constantly rediscovering things every day and that will carry on – I think there will be new discoveries made in each performance. I couldn’t be loving it more actually.

Are there any similarities between you and the character?

No, not at all. He was extraordinary narcissist. There’s this wonderful speech at the beginning where he talks about the fact that he must not be ignored. Clearly he wants to be on people’s minds and thought of all the time. We are the centre of our parents’ universe, I suppose, up to a certain age and there’s a horrible moment of discovery when you realise you’re not the centre of the world. You think you are, but you’re actually just the centre of your parents’ world. There’s a realisation that many have and many don’t, and Rochester stays believing he’s the centre of the universe because he can’t bear competition from the King and he hates the lack of change the King has made.

It must be great fun getting to play such a rogue?

It’s wonderful but it’s about the language as well. Stephen Jeffreys has written such a magnificent play and the language is very fulfilling and terribly enjoyable. It’s like doing a Shakespeare in many ways. It’s that enjoyment of language they had then that Stephen certainly enjoys. That for me is very fulfilling and rare as an opportunity – to enjoy the language so much and behave in the way Rochester does; to enjoy the excess and the danger and the threat and how he relishes that. It’s a really fun character to immerse yourself in.

Is there anything you’ve been intrigued or interested to learn about the character and time period from doing your research?

I keep learning things every day. I was told a story the other day about some truly heinous things he did, which I can hardly bear to repeat – but everything in the play is true. I was talking to Stephen Jeffreys (playwright) about the time Rochester left a very young man for dead, and the death was part of his making really. Rochester fled the scene, hid in the East End of London and became a quack doctor. He got the servants of the house to create medicines that were apparently made from coal and urine and administered them to patients. That’s a real lack of care and he messed up people’s lives for pleasure and fun. He seemed to have a lack of empathy towards anyone except himself and people at that time were rarely punished for the things they did. In the King’s court it seems they were so out of control and inebriated all the time. I think Rochester was drunk all the time to quell the lack of achievement in his life. He was terrible to his wife and he never fulfilled his ambition. It’s hard to find many redeeming qualities in him. I want the audience to like him, to enjoy him, and relish his absurdity but if you really do analyse the man and take him apart he’s not particularly pleasant. I’m studying that dark side to him, but at the same time I want the audience to enjoy watching this person.

Do you think that’s what draws audiences in – seeing someone behave so badly?

I suppose the play does do that, yes. We do enjoy watching that kind of thing, don’t we? Living out things we’d never dream of doing ourselves – things that are so far removed from anything to do with our lives. You ask the question ‘He’s so awful, why will people want to watch him?’ but the answer is people love seeing that kind of behaviour. And the truth is he did behave like that; it’s not a made-up story. In many places in the world people still do behave that way. There are still terrible people who feel they can behave in any way they like and treat people with such disdain and such a lack of love.

How is it working with director Terry Johnson?

He’s been wonderful. It’s been interesting going back on stage. I haven’t done it for seven years and you have that week before when you’re very panicky about it. But Terry has made it so comfortable. I’ve realised how important that is, actually, and how freeing it is to take risks and to gain slowly the confidence you need to do your best work – to take risks and challenge yourself. Terry had done the play before so he’s comfortable and confident. He knows what he’s doing and exactly what he wants and it’s wonderful.

Having been in the States making Preacher how is it being back in England?

It’s wonderful. I haven’t had much structure recently. I’ve been all over the place travelling with the promotion of Preacher so it’s been nice to be home again, to settle down and have some structure to your week. I remember now how important it is to have that. I adored every moment doing Preacher and I can’t wait to go back and carry on filming, but it’s chaotic and exhausting, shooting 15 or 16 hours some days. It’s a much more haphazard and chaotic life so it’s nice to be back home, seeing family and friends and being in my house – which feels peculiar after all this time but really nice.

Are you looking forward to getting back on stage?

I am actually. I had all that fear beforehand and there’ll be more of that. It wanes and rears its head again, but the stage is where it all began for me. I started on stage and that’s what I went to drama school for. It’s odd but quite comfortable. It feels like home and it feels natural rather than terrifying.

What memories do you have of being at the Theatre Royal Bath in Mark Ravenhill’s play Mother Clap’s Molly House in 2001?

I remember the audiences being the best audiences I’ve ever performed in front of. It went so well in Bath. It is an extraordinarily odd play, if quite brilliant, and it changes so dramatically halfway through, but people there really loved it. I can’t wait to be back in that theatre. By the way they reacted to that particular play I think this show is going to go down tremendously well. With the theatre itself I remember it being very big but also very intimate. It’s beautiful in Bath and I have a great feeling about us starting out there before the West End and gaining confidence with a really welcoming and all-embracing audience.

Since you made your stage debut in that production at the National Theatre what have been your career highlights?

It’s funny because my career highlight is getting that first job. I was in drama school, then a few weeks later I’m meeting Nicholas Hytner, then I’m getting a job in the Lyttelton Theatre at the National, then taking it to Bath. It was incredible. You leave drama school with a multitude of people warning you kindly, because they don’t want you to feel huge disappointment, that ‘It might not happen, it’s going to be hard, you may not work for years’. But I got a fantastic job doing a new play in the building that I continued to work in for many years – the National Theatre – and I loved it. It all made sense. You have moments in drama school where you’re thinking ‘What on earth’s going on here?’ Your friends are at university, meeting new people and living a very different life, while you’re pretending to be various strains of wind or animals. You have moments of questioning it and so the moment when it all makes sense – as I have felt again with this play – is such a rewarding sensation to have. So that first job is a highlight, although I also remember the letter saying you’ve got into drama school being so monumental. Then three years later there’s a phone call offering you a part. It’s completely magical.

Will you be exploring Bath in your downtime?

[Laughs] I have no idea what we got up to the first time. In fact I have no idea where I stayed. But I’m looking forward to being in Bath again. It’s a beautiful place. I know it better now and I love it.

Which roles are you most recognised for?

It’s all varied. It’s funny because you can normally guess when people are approaching from their age and their look what they’re going to mention. It goes in waves and it depends what’s on at the moment. I’m getting recognised for Preacher these days, which is nice because I’m very proud of it. But I get recognised for many different things like The History Boys because it ran for such a long time and a lot of people got to see that, especially when it was made into a film. Then there’s the Mamma Mia! fans who are all grown up now. They used to be 11-year-old girls and now they’re a totally different generation. And the poor parents who suffered being made to watch it six times a day by their five-year-old kids! But I love it when people talk about Mamma Mia! It seems to have brought joy to a lot of people’s lives, sometimes through quite hard times too they often say, and that’s a rewarding thing to hear.

It’s a big contrast to The Libertine, which just shows you’ve had a very diverse career…

I’m so lucky it’s turned out to be that way. Maybe it’s not true; maybe I’m exactly the same in everything. But I feel I’ve done a lot of different stuff and I love that. As I say, I’m very lucky.