Where can you find acts of simple kindness, nowadays? Not from the ideological, austerity-driven politics of the last six years argues Harold Pinter Playwrights Award winner Anders Lustgarten in this, his latest production, performed by the RSC.

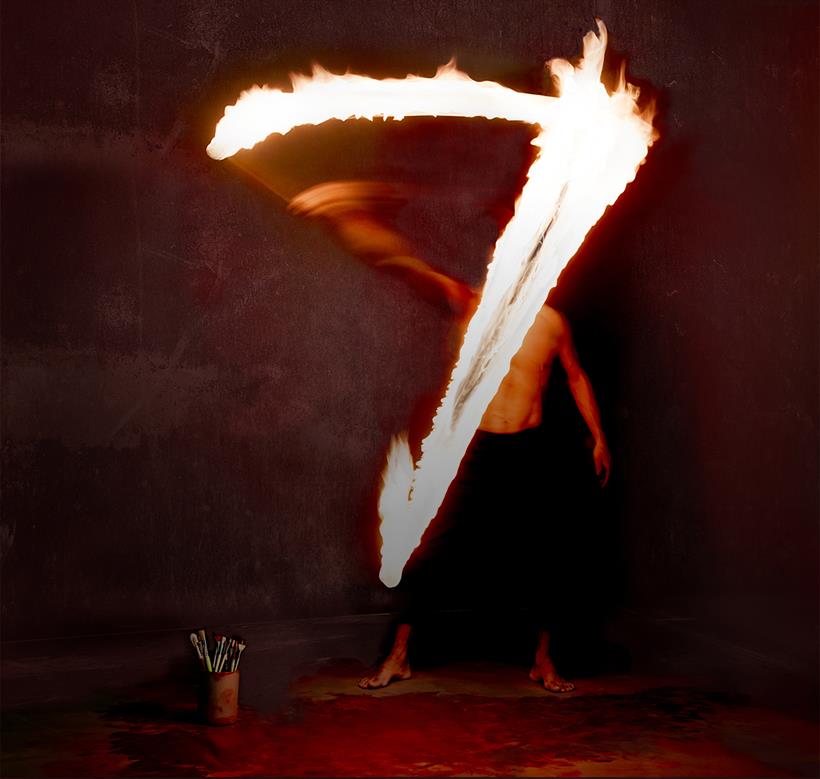

Drawing on Caravaggio’s painting, The Seven Acts of Mercy, as inspiration, Lustgarten’s play attempts a commonality between the seventeenth century painter’s relationship with power (nobles and the Church) and his depiction of the common man’s empathy to his fellow man, as outlined in Matthew 25:36-37, and contemporary down-at-heel lives in Bootle, Liverpool, where the pincer movement of Right to Buy and the Bedroom Tax combine to force out long term council residents, and ESA assessments drive the already vulnerable into penury and the food bank.

While the political left struggles to kickstart its political zeitgeist, the social iniquities being heaped on the country’s most vulnerable citizens by an increasingly unfettered and maverick Right are at least, you could argue, being catalogued, held to account, painted even, by the likes of Ken Loach and Lustgarten, where screen and stage have taken the place of canvas.

This Caravaggio is a man on the run. A murderer, he is dependent on the Church for his safety and his money while he performs his extraordinary trick of transforming those at the bottom of the heap: beggars; the ill; sex workers and even the dead, into iconic figures of goodness within his latest composition. His use of the real, not the ideal, is the transformative element. This is not a vanity project. He captures very ordinary people doing the things that distinguish us all from simple beastliness. This powerful thread is what Lustgarten has seized upon to produce his parallel play within a play, a pastiche of iniquity and inequality meted out by a political elite, untethered by divided opposition.

While Patrick O’Kane delivers a towering performance as the increasingly paranoid Caravaggio, Allison McKenzie puts in a dazzling shift as the prostitute and artist’s model Lavinia – a living metaphor for those at the very bottom who find themselves punished severely for daring to believe that life might promise more.

Snapping continually between Caravaggio and his battle to stay just the right side of danger, and the dwindling world of the old socialist, Everton-supporting and retired docker, Leon, played by the excellent Tom Georgeson, the play veers from betrayal to forgiveness, kindness to brutality.

It’s the brutality, both physical and mental, that seems to colour this production the most. Blood pours from Caravaggio’s head and Lavinia’s cheek, while gangsters rough up the Bootle dispossessed. All the while the dying Leon desperately seeks support for his grandson Mickey from his less principled and debt-compromised son Lee.

Together with some very heavy punctuation from the six hidden musicians, this is an uncompromisingly dark, testosterone-driven tale, save for a few delightfully humourous moments in which Leon indulges in some playful football philosophy.

In amongst all the shouting was a memorable and wonderfully understated performance from sixteen-year old T J Jones as Leon’s grandson, Mickey. Mickey learns from Leon what fine art can mean, what it can say to us. Setting out to record his own interpretation of The Seven Acts of Mercy as homage to his granddad’s love, Mickey experiences first hand just what Caravaggio was trying to communicate 400 years ago. ★★★★☆ Simon Bishop 10th December 2016