As we know, losing one of our faculties will often lead to one or more of the others becoming more acute. The great triumph for George Mann’s production is that this masked mime/dance piece, in eschewing the communicative wonders of verbal language, achieves creative effects in two senses of the word (‘acute’); for the actor the physical sense and for the audience that of perceptive understanding. The performers (George Mann and Deborah Pugh) achieve a physical articulacy that is perhaps only possible with the absence of speech. They exhibit a precision and clarity of movement I liken to going to the theatre and being able to hear clearly every word uttered by the cast (sadly not always the case). These skills allow them both to develop richly expressed and delightfully engaging personalities.

Whilst the title refers to a journey the piece is actually the narration of a sublunary paradise – the joy of an earthly relationship, recollected and reenacted following the death of the female partner. There is a striking moment as the (older) woman dies and her mask floats away to reveal the young woman in spirit, released from her aged body; the effect is very moving. The woman returns, whether in imagination or as a spirit is left to the audience, and the course of their life together is narrated in movement; their meeting, the growing attraction, their first home together, their first argument, the tragedy of a miscarriage and separation by war. It has a breadth and flow perhaps only achievable with the absence of dialogue and yet achieved without any loss of emotional impact. Emotions are strong and clear thanks to the exceptionally expressive faces of the performers. At certain times the action speeds up as time is compressed whilst at others it bursts into dance as joy seeks an outlet.

Forming no mere background or accompaniment is the accordion playing of Sophie Crawford. Together with a haunting kind of scat with lots of ‘da da das’, the effect is of an emotional and celestial navigation, perhaps even an intangible mis en scène for the unfolding story. Again, allowing the accordion to simply breath, the masks are given their own signature sound as they leave and attach to the faces of the performers.

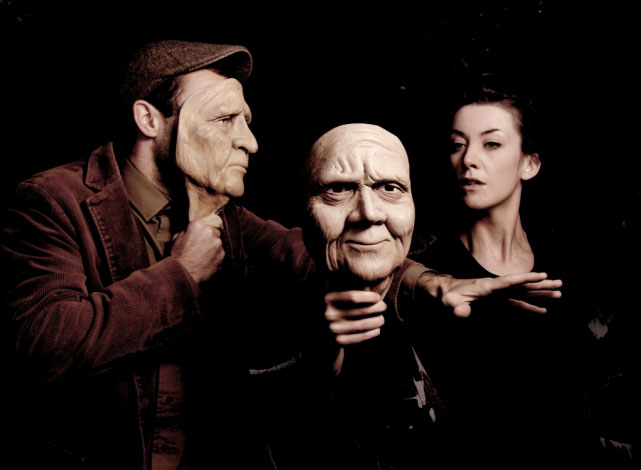

Mention must be made of the contribution of the masks, created by Victoria Beaton. Unlike the masks of classical Greek theatre and their descriptive, but fixed expressions (recall Lysistrata’s angry look) the two masks of the older selves of the characters are remarkably receptive to changing moods. Hand-held and close fitting, the performers eyes may be seen twinkling in the holes, giving them, under certain light, an uncannily realistic appearance. The positive (as opposed to blank) neutrality allows the audience to project onto the mask whatever the actors are showing through their bodies.

It is a remarkably selfless and accomplished piece of work on the theme of loss and loneliness, which reaffirms our faith in the power of storytelling using little but highly developed talent in a darkened room with a receptive audience. ★★★★★ Graham Wyles 6rh July 2017