Connoisseurs of acting need look no further than the present offering at the Ustinov, which is developing something of an addiction to the production of notable performances. (viz. Tanya Moodie, Kenneth Cranham, F. Murray Abraham to name but three)

The play is set in the artist, Lucian Freud’s, studio. At one point he refers to his great grandfather as being ‘the elephant in the room’, but for us in the audience that role is taken by the invisible, naked sitter, his interlocutor who he cajoles, bullies, charms, threatens and seduces to his will. As he examines the unnamed sitter (a she) it is with the gaze of an eagle about to devour its prey. A mark well made elicits a little wiggle of delight, the smell of the paint excites the anticipation of creation.

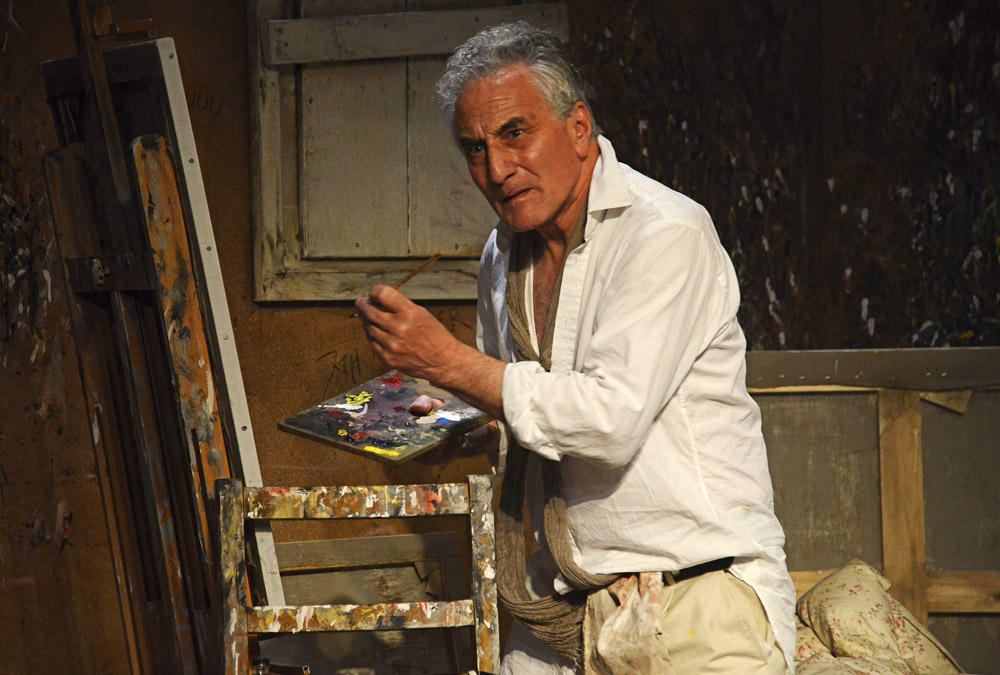

We often hear of roles being, ‘a gift of a part’, something only true in hands of an actor with the necessary talent of interpretation, and who in addition knows how to use it. Henry Goodman inhabits the character with an easy familiarity that gives his fluctuating moods a central spring rather than some loose connection. A more convincing character study would be hard to find. Carla Goodman’s set, a recreation of Freud’s studio, seems to fit like a glove. At one point he nips out of the studio, mid sitting, for a quick shag with an unseen visitor – presumably the one who threw a message, wrapped around a stone, through his window. Of course he does.

The piece is built with series of recollections from an extraordinary life in which the stench of Nazi anti-Semitism has waned to a faint odour, which clings still to a (Germano-Jewish) English gent: from the ten year old boy fleeing Nazism to the man of prodigious sexual appetite, dogged in the media by an unlooked for fame (like Augustus John before him) that owed more to his lifestyle than his artistic output. Writer, Alan Franks, has chosen his anecdotes with the same care that he attributes to his subject’s choice of colours. So we have the grandson of the ‘most famous Jew in Europe’ who, as a lad, met Hitler and went on to become one of the most celebrated British artists of the second half of the twentieth century, managing on the way to raise a laugh from Queen Elizabeth II during a sitting that was to earn opprobrium for a portrait that gives her the look of one who has single-handedly dragged the nation through the 20th century.

Tom Attenborough’s pulsing direction, which constantly pushes one off balance with sudden yet explicable changes of mood, gives an intense actuality to a compelling portrait.

In the royal picture the Queen is depicted with a face that, like many of Freud’s other portraits, appears to have been moulded by time and excoriating experience. Messrs, Goodman, Franks and Attenborough have done no less for Freud himself.

Cleverly Franks makes of his material more than the sum of a series of anecdotes, managing even to conjure a kind of dramatic coda that makes us re-evaluate what has gone before as an assault on privacy and an affront to the creative process itself. Like many a worthy biography it leaves one with not only a deep insight into the subject, but with a reinvigorated desire to be.

Mr Goodman has produced an exceptional, complete, varied and nuanced performance that is the match for any artistic endeavour in any medium and will justify all laurels that must surely come his way. ★★★★★ Graham Wyles 10th August 2017

Photo by and © Nobby Clark