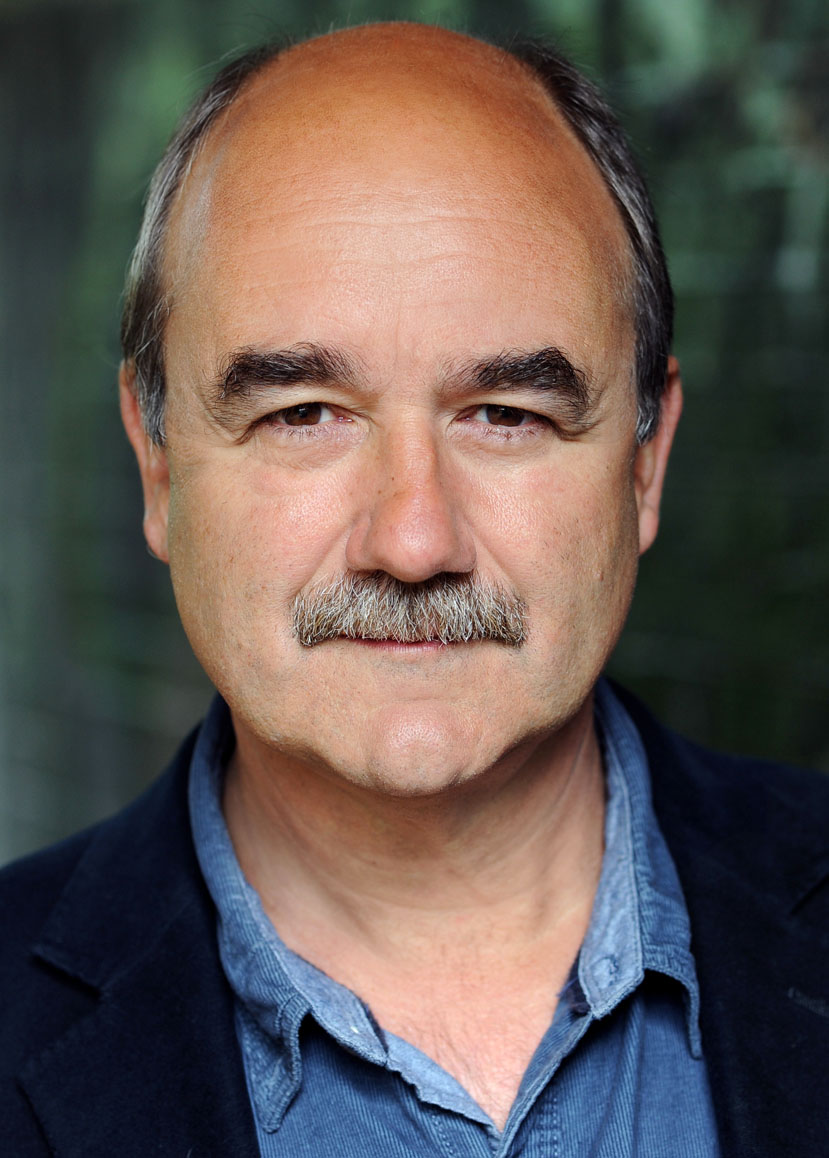

DAVID HAIG is appearing as The Reverend Lionel Espy in David Hare’s award winning play RACING DEMON which continues at the Theatre Royal in Bath until 8th July.

What attracted you to Racing Demon?

I’ve always loved the play. It’s a great play and it’s my favourite of all David Hare’s plays. One of the brilliant things about Hare’s writing over the years is that he captures the political zeitgeist of any one time but his really great plays transcend that and this one does. Yes, it’s about the Church of England during Margaret Thatcher’s time but he presents us with these incredibly endearing characters. He confesses himself that while he was researching it he sort of fell for all these people he interviewed – vicars who were working in inner city areas on really rough estates trying to do ‘good’, trying to inject their generosity of spirit into these people’s lives. The play brings that across and it also has a very good sort of thriller element just lurking under the surface.

How would you sum up the character of Lionel?

He’s a spiritual social worker but a flawed personality, as we all are. He has a twinkle in his eye which he falls foul of. He’s gentle but flawed.

What are you most relishing about playing him?

It’s about contrasts because I’ve just done Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, which is by another great writer of course [Tom Stoppard]. This crazy, anarchic, sort of Elizabethan gypsy I was playing for the first half of this year – the contrast between that wild character and this very subtle, gentle character is just wonderful.

What do you see as the key themes of the play?

Whether there is validity or worth in the work the church does in this day and age. What it means to be good or the opposite of that. What it means to be extreme and what it means to be moderate. What it means to be liberal and what it means to be reactionary. Relationships and what it means to love somebody and what it means to betray somebody. All of those elements come out in the play.

How does it feel to be launching Jonathan Church’s first summer season at the Theatre Royal Bath?

Jonathan and I go back a long way so it’s terrific. I did a lot of work at Chichester when he was there and he’s producing my own play Pressure, which was on there two years ago and we’re going to do it again next year. The new play I’ve written he’s sort of in charge of and is sending around at the moment. We have a very good working relationship which has been going on for a long time. The fact he’s taken on this summer season, I can’t think of anybody better really. Sir Peter Hall had a certain cachet that brought out some really interesting work and I’m sure Jonathan will do the same. Now he’s left Chichester he’s grabbing on to some really interesting things around the country, some interesting projects, and this is one of them.

How would you describe your working dynamic with Jonathan Church?

The interesting thing is that although we’ve worked a lot together it’s always been as somebody who runs a theatre, a producer or whatever, and this is the first time he’s ever directed me. It’s very exciting for both of us and he’s terrific. He knows the play incredibly well, he loves the characters, he likes the cast of actors and there’s a great communication between us all. I’m loving it.

Why do you think David Hare is so revered as a writer?

Because he’s had the courage and the prescience to sort of click into, as I said, whatever the political zeitgeist is at any one time. Like all great political writers – and I put people like Bertolt Brecht in the same category – his great plays transcend that and you have this electric mixture of something that’s commenting on society but is also humane.

As a writer yourself has he been an inspiration in any way?

All the great post-war playwrights have been an inspiration, inevitably. Certainly David Hare and Tom Stoppard are two of my writing heroes so it’s extraordinary to do two great plays by them in a row.

You’ve appeared at the Theatre Royal Bath several times. What are your fondest memories of performing there?

I’ve got a lot of fond memories, mainly of sitting in the dressing room waiting to go on for a vast range of different plays. It’s such a great atmosphere there and it’s a beautifully designed theatre. I suppose The Madness of George III is the one I remember most fondly because it’s the one I remember in my career most fondly.

What are you most looking forward to about being back in Bath?

What is there not to like? There are many beautiful cities in this country, and some of them I haven’t seen I’m sure, but to me Bath is the most beautiful city I’ve been to. The stone, the feel of the buildings, the feel of the city, the water, the hills – it’s wonderful and I’ve always loved the South West of England anyway because [laughs] anywhere that’s just a fraction warmer is always a good thing.

When your busy schedule allows for some spare time is there anything you enjoy doing in Bath or is there anything you’re planning to do on this visit?

I really enjoy just walking around, sitting in a cafe, having a coffee, reading a novel, writing a few lines, deciding they’re bad, getting up, walking to another cafe and doing the same again.

Is there anything about Bath audiences that makes them special?

There is, yes. It’s rather like Chichester, where I do a lot of work. If you go to a theatre where an audience is incredibly loyal to the theatre itself, to the institution, and are prepared to give time to any product or project that comes in you develop a relationship with them. Because I’ve worked at the Theatre Royal Bath four or five times now you do feel the audience welcomes you and is ready for what you’re next going to offer them. That’s a great feeling.

Given your extensive stage work, what have been your theatre highlights so far?

They go over a long period so I’m sorting of plucking them out of the air but, as I say, The Madness of George III [which opened in Bath] is a real highlight. There’s also Angelo in Measure for Measure, weirdly perhaps because it’s not necessarily something people would remember but it was the only time I’ve worked with Trevor Nunn and he was at his peak at the RSC. The character was just such a fascinating mixture of malevolence and sexual greed and nastiness with a sort of warped morality somewhere in the background. Our Country’s Good in 1988 was the first time I was nominated for and got an Olivier Award and I loved the play and the whole experience of doing it at the Royal Court directed by my sort of guru Max Stafford-Clark. And I really loved the one I’ve just finished, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. The Player is one of the great roles but I didn’t want to do it in the conventional way it’s usually done as a mellifluous actor/manager/luvvie. I was very determined that this was a guy who lived off his wits on the street, working class, rough and ready, a gypsy and pretty ambivalent sexually – just a complicated, rough-edged guy – and they were absolutely game because they wanted a different interpretation. I was given carte blanche to do something I knew hadn’t been done in that way before. Daniel Radcliffe [who played Rosencrantz] and I go back because I wrote My Boy Jack all those years ago and then filmed it with him in 2007. It was ten years almost to the day since we’d worked together before and it was great to work with him again. I’m incredibly fond of him. He’s a wonderful guy and a talented actor and we get on very well.

You have also worked extensively in film and television. Which of those jobs have you most enjoyed?

Eventually getting My Boy Jack made – writing it, being a producer on it, acting in it. It all came together in a sort of mass of coincidences of timing and nothing else has come close.

Racing Demon premiered in 1990. Why do you think it still resonates today?

You look around this complicated society where the church seems out of touch, as my character says, and is struggling to get through to people who are just struggling through life. It has an incredible resonance about whether the church still seems to have some kind of importance. Also when is religion not at the centre of our lives? I don’t want to get heavy about it but here we are again in a fundamental religious conflict which, as far as I can see, could be with us for another 100 years.

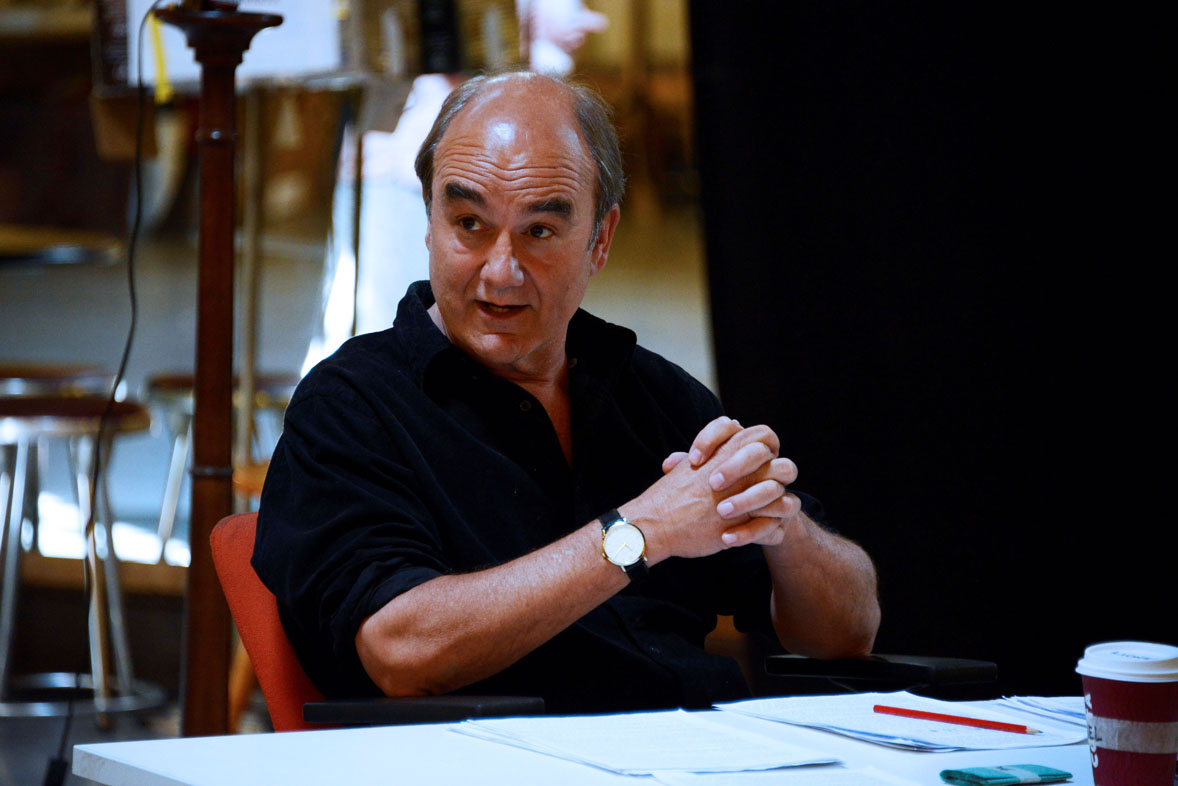

Rehearsal photograph © NOBBY CLARK