20 – 28 September

Adapted by Ryan Craig and directed by Lindsay Posner, this version of Orwell’s 1984 has some impressive strengths. Appropriately for a story where camera surveillance features so prominently, one of those strengths is the clever use of video technology. Before the play commences the stage is empty, save for an enormous TV screen within which there is an electronic eye which scans the audience, caught within its baleful, glassy stare. Nine of the cast of sixteen actors appear solely in pre-recorded footage on that screen, seamlessly integrated into the action. Plaudits go to video designer Justin Nardella and associate video designer Stanley Orwin-Fraser.

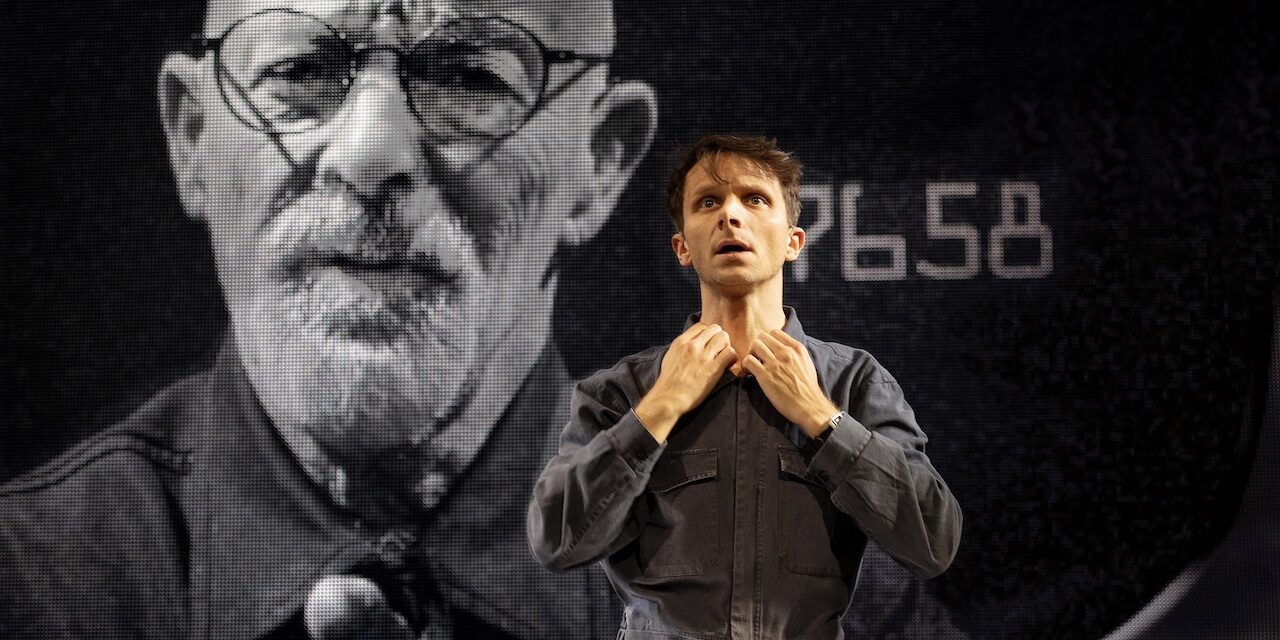

There are strengths too in the central performances. Mark Quartley depicts Winston Smith as an apparently bland and none-too-well ‘everyman’, a government employee in Oceania who rewrites history to meet the ruling party’s needs. The bombing of an innocent wedding party is transformed at his keyboard into the targeted elimination of military foes. Sound familiar? Winston’s one act of rebellion is to keep a diary, which he furtively hides from the all-seeing eye of the telescreen. Winston becomes more actively rebellious upon encountering Julia, played with earthy matter-of-factness by Eleanor Wyld. That she might inject some real life into Winston’s monochrome existence is perhaps symbolised in the blood-red sash she wears around her waist.

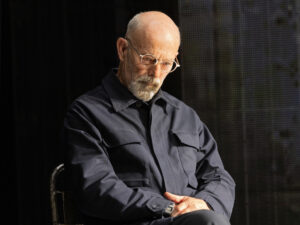

When Winston is summoned into the presence of party official O’Brien, he believes he has met a fellow rebel at the heart of the government. In an understated performance Keith Allen presents O’Brien as quietly avuncular and sympathetic. There is little if any hint of just how dangerous he really is.

By the interval all the elements of the story that will eventually lead to Winston’s downfall have been set in place. However, the rapid cutting from one brief scene to another precludes any sense of gradual rising tension, so the first half suffers from a flatness in tone. Another problem lies in the difficulty of expressing some of George Orwell’s ideas on the stage, such as ‘Newspeak.’ This was so important to Orwell that he explained it in a lengthy appendix. Here this concept is only touched on, so we see Winston being given instructions to expunge all adjectives from his writing, but why the authorities demand this is left unclear.

The second half is far more dramatically effective, and features a brave, gut-wrenching performance from Mark Quartley as the now imprisoned Winston. He is seen sharing a grim, bare cell with Parsons, his one-time neighbour who had always been one of the party faithful, yet who has been betrayed by his little daughter. In a touching performance David Birrell vividly conveys Parsons as the hapless, brainwashed victim of a cruel system that he still pathetically adheres to.

Winston is more resistant, but in a scene of dreadful electric shock torture, O’Brien both literally and metaphorically strips him bare, until he finally accepts that he can see five fingers when he is shown only four. ‘I want you to see my truth’ says O’Brien, in a chilling moment that has more than a little contemporary resonance. As for what happens in the dreaded Room 101, Lindsay Posner has bravely left much to our imagination .

In a world of CCTV ubiquity, where many of us can barely manage a minute or two away from the screens of our mobile phones, and where ’reality’ TV shows and social media render any notion of privacy as old-fashioned, Orwell’s 1984 still has a great deal to say to us. This technically proficient production takes a while to warm up and some key ideas lack clarity, but ultimately it packs a powerful punch.

★★★☆☆ Mike Whitton, 25 September 2024

Photo credit: Simon Annand