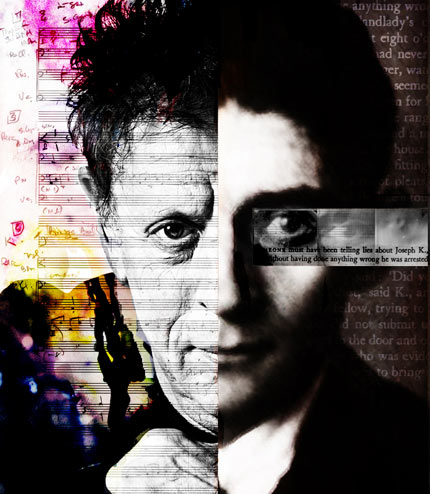

Franz Kafka’s novel, The Trial, has been adapted for radio, for film and for stage, particularly the latter. It focuses on Josef K, a man who awakes to find himself under arrest for a crime that no one will specify and one he himself cannot remember. Now Philip Glass tells the story in the guise of an opera, or what seems rather more like a piece of sung theatre with musical accompaniment, with the careful libretto written by Christopher Hampton. The Music Theatre Wales Ensemble does very well with what they are given. Amiable Johnny Herford takes the central role.

Kafka’s concept of a dour and delimited totalitarian state is realised here with what appears to be a wavering tone, one that apparently is intended to be “hilariously funny” (as described by Glass) but errs more on the side of raising a smirk.

Part of the problem is that tension is not immediately present within the performance, tension which, should it be broken in a timely fashion with precise gallows humour, would surely lead to guffaws. This is emblemised and enforced by Willem and Franz (Michael Bennett and Nicholas Folwell) in the opening scene, as they appear as witless police jesters attempting to instil fear rather than parodic absurdities, as they should have been. They do not make you laugh, they may make you smile. The music is non-confrontational to the same degree.

The second act is pitched far more cutely, buoyed by the tremendous performance of Paul Curievici as the ridiculous Titorelli. His comedy is apparent, his grin is wide, yet there is a penumbral source of consternation, a creeping dread. The mercurial quality that the production is attempting to achieve seems most concrete in Curievici’s performance, as opposed to the broad strokes of Bennett and Folwell.

This crucial sense of discomfort remains present till the curtain falls, thankfully. When the ludicrous is rendered plausible enough to make people anxious of its reality, that is when the performances shine here.

There is a quasi-sexual current one could trace throughout much of the production; something base and animal. Neither raw sensuality nor brutality is actually ever exhibited, however. At various times each of the performers looks like they could rip one another’s clothes from their bodies and ravish them, but alas, this level of passion – or, indeed, action – is never achieved. Not even the kissing between Josef and Leni (a strong Amanda Forbes) is real.

Everyone is far more passive. Perhaps that is the point. The awkwardness, the Deutsch-Dickensian costuming, the women as objects, the silly beards: maybe they are to lead us to deduce to something wrier is going on here.

Simon Banham’s design is accomplished in its simplicity. Three walls, plain save for some mottling to facilitate the space operate seamlessly as indoors and outdoors. They stand incredibly tall around the stage, which is sparsely furnished and amazingly spare with colour. The subtleties that Ace McCarron’s lighting draws from this bare set are what should be praised as most consistently affecting though. The show is visually gorgeous.

It is an enjoyable, perverse and kinetic production, one held back by its unwillingness to be more perverse. One imagines The Trial to grab its audience by the throat, not by their shirt-collars. ★★★☆☆ Will Amott 11/11/14