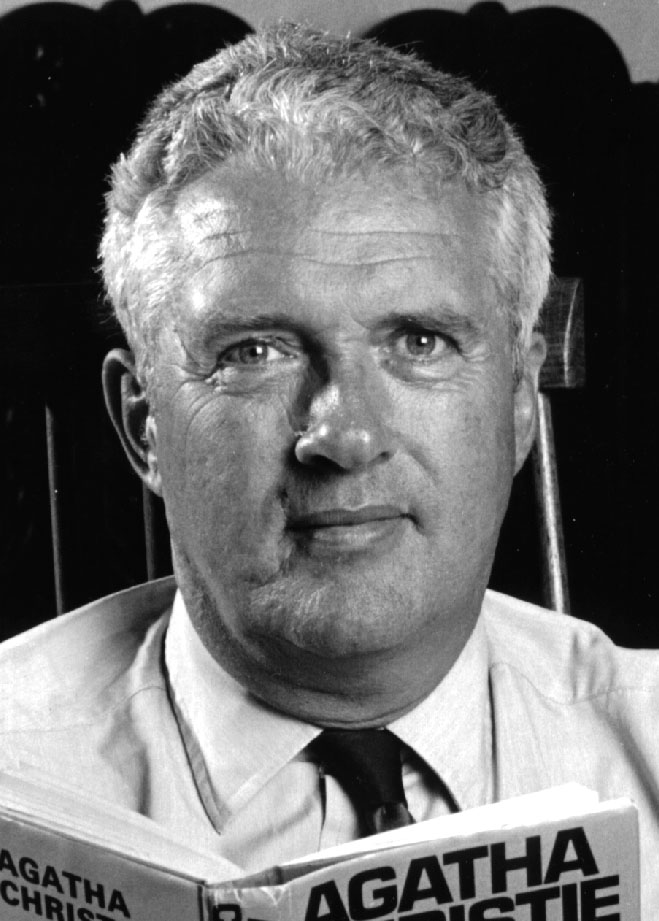

MATHEW PRICHARD, grandson of Agatha Christie, talks about his reminiscences of la grande dame whose most famous whodunnit, The Mousetrap, she gave to him as a ninth birthday present. The play is at Bristol Hippodrome from 9th August.

I suppose it took some time for it to sink in that I had a famous grandmother known to the world as Agatha Christie. I first remember her during the years when I was at preparatory school and her house at Wallingford was nearby. We used to have enjoyable ‘exeats’ on Sundays and it was, I think, then that the first glimmers of truth came through. Very sensibly, the headmaster of my school insisted on initialling all books that came into the school. I came back from Wallingford clutching the latest Agatha Christie and wondering, quite genuinely, whether the Head could possibly find any reason for withholding the coveted signature. He never did! There was, however, one occasion when my book took a terribly long time to re-appear. Later I realised that the headmaster’s wife had taken the opportunity to read it!

In such small ways, therefore, did I become aware that I had a talented grandmother. Not that it made a great deal of difference to me. She was just a marvellous grandmother and someone nice to have around. I think perhaps there were four things which, more than anything else endeared her to me. The first was her modesty. To the outside world I suppose this appeared as shyness, but to us she was always infinitely more interested in what we were thinking and doing than in herself.

She could manage to write a book almost without one noticing and sometimes she used to read the new one to us in the summer down in Devonshire. She did so partly, I suspect, to test audience reaction, but partly to entertain us on the inevitable wet afternoons when, no doubt, I was rather difficult to amuse! We all tried to guess, and my mother was the only one who was ever right. I think most of my friends who met her during those years were quite astonished that such a mild, gentle grandmother could really be the authoress of all those stories of intrigue, murder and jealousy.

Her next great characteristic was her generosity. It is by now well-known that she gave me The Mousetrap for my ninth birthday. I do not, I’m afraid, remember much about the actual presentation (if there was one) and probably nobody realised until much later what a marvellous present it was, but it is perhaps worth remembering that my grandmother had been through many times in her life when money was not plentiful. It was therefore incredibly generous of her to give away such a play to her grandson, as in 1952 her books were only approaching the enormous success they have now become. It is also a mistake to think of her generosity only in terms of money. She loved giving pleasure to others – good food, a holiday, a present, or a birthday ode. She loved enjoying herself, and also to see others around her enjoying themselves.

The third thing I always enjoyed was her enthusiasm. Despite her modesty or shyness, it was never far below the surface. I think she always had a love/fright relationship with the theatre. Although I am sure she found experience very wearing, she always enjoyed other people’s enthusiasm for her plays and found it infectious. I went to The Mousetrap several times with her in varying company – family parties, girlfriends, and the Eton cricket team when I was captain in 1962. I would say we all enjoyed the play and my grandmother’s company in equal measure. But she was enthusiastic about other people’s plays as well, about archaeology, opera and perhaps above all about food! In short, she was an exciting person to be with because she always tried to look on the good side of things and people; she always found something to enthuse about.

When I had the pleasure of taking my own children, aged twelve and eleven, to The Mousetrap for the first time they enjoyed it tremendously, and crossed off assiduously in their programmes those whom they thought couldn’t have done it (the real culprit was excluded at an early stage!). It was great evening for me, and would have been, I am sure, for my grandmother had she been there. I think it tells us something about the success of the play, too: it contains so much for everybody – humour, drama, suspense and a jigsaw puzzle – suitable for all ages and taste; regrettably not too many plays on the London scene can say the same, and I sometimes feel that actors and actresses, anxious like everybody else for employment, must wish that there were more plays with universal appeal like this.

My grandmother died in January 1976. My family received hundreds of letters from all different walks of life and every part of the world, and I have never seen such a uniform expression of devotion and admiration. No doubt that was because she was a kind, generous and devout person, and preferred always to believe the best of people. She never had an unkind word to say about anybody. We were all left with many happy memories and, of course, all her books and plays, which I am sure will be enjoyed for many generations to come.

It would be remiss of me not to say, on this occasion, something about my grandmother and Peter Saunders. I myself remember Peter as a persistent producer of medium-pace off-cutters in my boyhood cricket days at Greenway in Devon. I am sure it is no exaggeration to say that many Agatha Christie plays would never have been written at all but for his judicious mixture of persuasion, encouragement, confidence and pleading. She adored it all, and certainly, we all recognise what The Mousetrap owed Peter in its earlier days. His confidence in it never wavered and its longevity is as much a tribute to his great partnership with my grandmother as to anything else.

It is inevitable perhaps that my own impressions of my grandmother are rather personal ones. She was, above all, a family person and through everybody, from the literary world, from the world of archaeology and from the stage has good reason to be grateful to her it is her family who have the most to be grateful for – her kindness, her charity, and for just being herself.