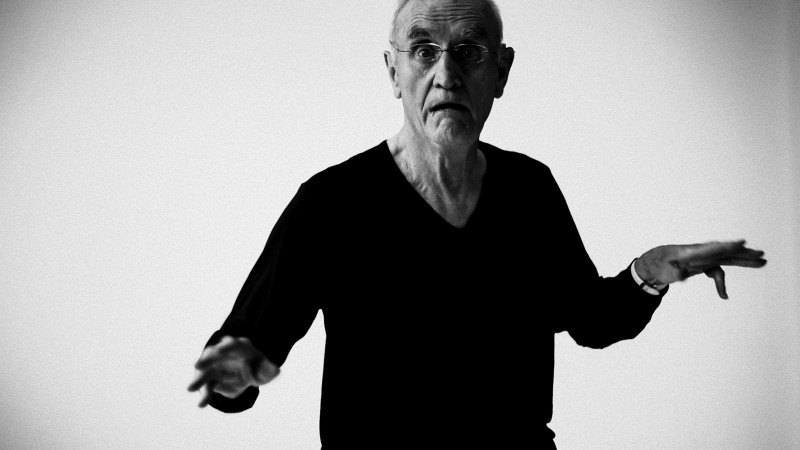

Tim Barlow has had an acting career spanning over forty years, since he left the British Army. His life both before and since that vocational turn has been colourful. You could say that it’s been the sort of life one might write down in memoirs. But colour isn’t always enough. Memoirs can be written about any kind of life—big, small, glamorous, simple, fraught, or easy—with the right knack. Barlow is a charming enough presence on stage, and the different elements of HIM work fine on their own, but what they amount to is neither cohesive nor particularly powerful.

On stage, the audience sees Tim Barlow, sat stage left with a large bottle of water, and bassist Sebastiano Dessanay, stood stage right with his instrument. (All the music is excellently chosen, it should be said.) In the middle, at a slight angle, hangs a large screen on to which black and white film is occasionally projected.

The impetus for HIM, writes Sheila Hill, the lead artist and writer, was a desire to create a work that melded the worlds of theatre and visual art, to put forth a show that offered subtlety and focus. And that goal is met, to a degree. At points the production is truly lovely, as the elements of storytelling, filmed material and music bolster and build off one another.

But at other points, odd choices were made. Thematic through-lines seem to have been discounted, in favour of Tim himself being the only constant. Early anecdotes fizzle out. At one point the supremacy of non-verbal communication is lauded, awkwardly contradicting the actual balance of speaking, music and film in this very production. Also, to have Tim walking through nature, all in monochrome, gazing wistfully around and then smiling directly to camera seems to me to not really understand the power of film, its unique and distinct qualities. I hesitate to call it amateur, but it felt very “student art film.” Viewers have seen that sort of material dozens of times before, which is so obviously intended to cue certain emotions, and the result is void of impact.

The program implies the project is the work of a group of friends. An editor (an outsider’s perspective) would benefit the project greatly.

It’s a shame, as well, as much of the filmed material was brilliant. Both the opening and closing filmed bits are joyous and vital, and the long clip in which a close-up of Tim’s face is matched to the gradual escalation of the noises of the world around him packs a real punch. The material about his hearing is some of the strongest, and one must recognise the importance of work that celebrates people with hearing loss and relates their often invisible experiences to an often ignorant public.

Hearing someone describe how they were falling asleep a lot (and an aside about a hungry cat) does not sound like it has the power to transfix, but the best anecdote of the night is about exactly that. Barlow finds his stride, and alternately has the viewer on edge, and amused. He’s good before this, getting better as the show proceeds, and this is him at his absolute best. It’s also the anecdote the show closes on. A smart choice.

There’s a warmth to HIM that is undeniable—ditto for Barlow himself, never more so than when he is dancing, which conjures genuine delight—but the disjunction of its parts means that it (somewhat illogically) feels both too long and too short, and the result is only relatively diverting. ★★★☆☆ Will Amott 7th October 2016