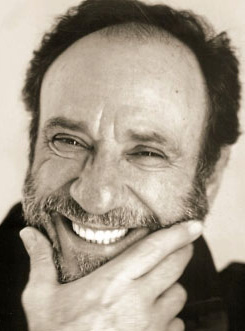

F. Murray Abraham played Benjamin Rubin in Daniel Kehlmann’s THE MENTOR at the Ustinov Studio in Bath in April and May 2017. Here he talks about the play and his role in it as well as his distinguished career in the United States both on screen and stage.

F. Murray Abraham played Benjamin Rubin in Daniel Kehlmann’s THE MENTOR at the Ustinov Studio in Bath in April and May 2017. Here he talks about the play and his role in it as well as his distinguished career in the United States both on screen and stage.

What attracted you to the character of Benjamin Rubin and The Mentor?

First of all there’s nothing like doing an original play – nothing. I love the classics and I do them but there’s nothing like trying something out for the first time. It’s thrilling and also it’s a great part, and a great part for me is where you get the chance to try everything you have to offer. There are so many so-called kitchen sink dramas and it seems to me that the theatre these days is looked on as a stepping stone for movie or television production so it’s scaled down to a camera size rather than being designed to a size that will fill a stage and fill a theatre – a big gesture, a Cyrano, something bigger than life. This play addresses that kind of thing. It looks naturalistic but it deals with big ideas and the role gives me a chance to use the range of my voice, which is important to me.

Benjamin can be quite cantankerous. Is that fun to play?

[Laughs] It’s fun but it’s also funny. It’s got a good balance. Yes, he’s cantankerous but in a way it makes you think ‘It’s ridiculous, it’s funny’. And I like being funny. I was funny for most of my early career until I did Amadeus, then I became known as the bad guy.

Have you ever met or worked with people like him and are you basing your performance on anyone?

He’s an amalgam of several people. There are some people who are just kind of sour and the difference between them and this guy is that he did come up with the goods once. I don’t know if you’ve ever fallen in love and thought ‘This is it for the rest of my life’ then the next time you see that person it doesn’t exist any longer and you think ‘My God, was it just one-sided? Was it real love?’ and you spend the rest of your life looking for it again. That’s got to be a tragedy – to have known and tasted love and never to find it again but to know it’s there. That’s what this feels like; as a creative person it’s got to kill you to know it’s possible and you’ve done it and ‘Why can’t I do it again?’ That’s why I go back to the theatre. I do movies and television to finance the theatre, so I can do King Lear, so I can do the great roles.

Were you familiar with the work of writer Daniel Kehlmann prior to this?

No, I wasn’t. He sought me out and now I’ve read his novels [laughs] one of which is titled F so I had to read that one. It’s telling that so many themes repeat in his work, like what we are examining on stage – the fact that the work is all that matters. That’s really hard to swallow but that’s what the lesson, I think, of this play is for every artist and for everyone. The example is not only for artists who happen to be in the audience, it’s for any person who questions the value of what they do. It’s as though when you do a generous act, if you’re doing it and you expect something in return then how generous is that act? It should be enough that you did it. It’s yours. You did it out of the goodness of your heart and your soul. I feel that strongly, by the way; I really do. What I have to fight against is that other inclination that we all have, especially actors or anyone who displays themselves for adulation and adoration, which is when I do something I’m checking myself out. That’s anathema for an artist. You can’t keep monitoring, you’ve got to trust yourself and do the thing and trust that it’s going to be OK. At this stage in my life I’ve been doing this for so long that I can take chances and if I fail it’s acceptable, it’s OK, they still get their money’s worth.

Who have been your real-life mentors?

I grew up on the border of Mexico and I grew up with a Mexican-Texas accent and when I discovered I wanted to act I had to get rid of it. My mentors became recordings, which I have still – discs of John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson. They were my three idols, which is a funny thing for a kid from El Paso, Texas, to be listening to – them and John Barrymore, who I also loved. They were my mentors and further along there was my teacher in high school and my teacher in New York City, Uta Hagen, and of course there were the great actors. Marlon Brando was a very big influence. But with personal mentors I didn’t have that kind of luck I’m sorry to say.

Have you been a mentor to anyone yourself?

I teach from time to time and if that’s mentoring then I have, yes. It’s at my leisure; I do it because I love it. I’m pretty good at it but I only do it once in a while. [Laughs] I tend to throw people out of the class and you can’t be a professional teacher and get away with that. I do it once a year, big classes, at the Atlantic Theater Company in New York, about 200 people – directors, writers and actors mostly. If you were to gather a survey together you’d hear quite a diverse response. Some of them adore me and some of they go ‘Are you kidding?’

You’ve performed in Bath before (in Tolstoy in 1996). What are you most looking forward to about returning?

That was a very unhappy experience. It was badly produced and there were promises made that were never forthcoming. When I first read the play I was interested because Tolstoy is a great role and I love the Russians, but it was a very early play by the playwright and he promised he was going to rewrite a whole bunch of stuff but he never touched it. It was a small disaster. I got to see Bath and London and people seemed to enjoy the tour, but when it got to Bath it sort of fell apart. But it’s an extraordinary place. It’s a breathtaking city and a breathtaking part of the country. I find the people in Bath to be lovely and they speak with a clarity I understand because [laughs] I don’t understand all Brits. I feel very comfortable here. It’s a very welcoming place and a great place to walk around. You just have to get here early enough in the day to avoid the tourists.

Having acted on both stage and screen, what do you most enjoy about live theatre?

It’s mine. I’m completely at home on the stage. There’s no longer anyone between me and the audience. There are no editors, there are no people to say ‘Cut. Change this and change that’ or voices dubbed in. If I feel I want to change the rhythm of something I will, if I want to change the range I will, and the actors around me trust me enough that they put up with it – at least most of them anyhow. But I’m not doing anything wildly divergent; it’s always with the play in mind. I’m extremely, extraordinarily generous as an actor and it’s because I want the best for the play. That’s what I love about the theatre, aside from the connection with the audience of course. There’s a recklessness and a wildness about the stage and I think that’s why people go to the theatre. They like the surprises. They like the possibility that that actor can come off the stage and walk right up to them. That tickles me to death. Zero Mostel used to do that; he used to go out and sit in their laps during the performance. It’s the primitivity that I like and the idea that what we’re doing hasn’t changed since the cave days. There must have been some sort of comedian in the old cave days. How did they get light into a cave? They cared enough to get a torch in there and they painted the walls. Art was essential to their lives. What kind of dedication was that? And the idea that we go into this dark room and we bring our lights in, just like they did, and then we listen to these people talk in front of us. It reminds you of the humanity; you identify with these people because you see them, you hear them, you smell them. That’s the value of the theatre, particularly of a small theatre. It’s very intimate and very dangerous.

You’ve played so many formidable characters. Do people expect you to be like that in real life?

Yes they do. They’re afraid to approach me on the street. It’s pretty funny because I’m probably the nicest man most of the time.