It would be difficult to fault this play in any particular: the writing, acting, directing, setting and lighting are all of the highest order. There are playwrights who, having reached a kind of mastery over their art can begin to play with the audience’s expectations. As in his previous play, The Father and in a different way The Mother, a sympathetic and revealing examination of a disintegrating mind – here through dementia – has us searching for solid ground from which to view and understand events. No sooner do we think we’ve got it sussed than the sand begins to crumble beneath our feet and uncertainty takes hold. And it’s a trick the writer pulls off multiple times within the space of an extended one act play – the latest in Florian Zeller’s suite of plays about mental fragility.

At the outset it is not clear whose story we are witnessing: that there has been a bereavement is at least clear(ish), but beyond that is a fog. We become as disorientated as, apparently, are the characters, with the consequence that we want to know more, we’re pulled into the action by wanting to know, not what happens next, but what’s going on? In The Height of the Storm we are witnessing a life seen as if reflected in a broken mirror; some shards reflecting the here and now and others different parts of the past that fit together haphazardly, but all, confusingly, viewed in the complex ‘now’.

What makes the journey emotionally draining for the audience is that it is not a dry piece of philosophy. We are forced to ask, ‘What is real?’, not in any clumsily metaphysical way, but at the human level of perception where these things matter and have deep emotional consequences for all concerned, the coalface of human interaction. It is remarkable writing aided and abetted by the crisp English translation (from French) of Christopher Hampton.

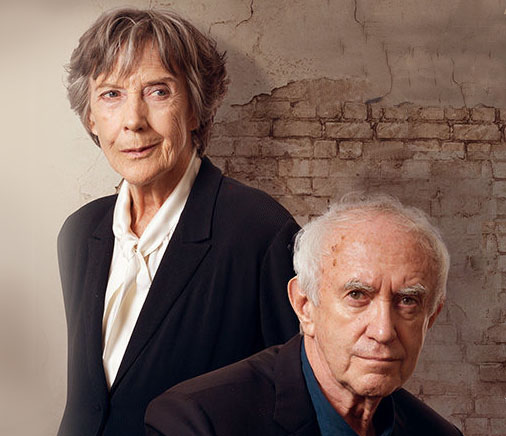

If Florian Zeller does nothing else he writes (to use a phrase of Noël Coward’s) cracking good parts for actors. You’d have sore feet before you’d walked far enough to find better acting (if it exists) than that of Mr Pryce and his co-star, Eileen Atkins. Ms Atkins acts in drypoint, transfixing us with detail and delicacy. With her the art is in appearing to be coasting whilst all the time being moved by hidden currents of Atlantic-strength pull. Mr Pryce, no less a master of intaglio, gives us a picture of dementia related confusion that makes one (him and us) want to scream at the world with, paradoxically, an excoriating clarity. The result in both cases is deeply affecting.

In Zeller there are no supernumaries, no spear carriers, each character pulls their weight. The two daughters (Amanda Drew and Anna Madeley) anchor events in the realities of family politics and emotions whilst family outsiders (Lucy Cohu, James Hillier) raise questions, provoke doubts as fragments of the broken mirror.

One could cheerfully throw the book of superlatives at this production without fear of over praising it. From top to bottom it is a gem.

★★★★★ Graham Wyles 19th September 2018