Contemporary theatrical re-imaginings of epic poetry date back to Aeschylus’s Oresteia, literally as old as Western theatre itself. Yet, as Inua Ellams demonstrates in The Half God of Rainfall, the epic tradition continues to provide abundant material for the stage. For his take on the shenanigans of the Olympian gods, Ellams takes us away from the Greek amphitheatre to the Nigerian basketball court. On the one hand, he does not take god-like matters too seriously. Something of a saving grace, if you excuse the pun. Yet his representations of the gods’ disregard for mortals is unquestionably earnest, indeed poignantly so. In this way, he both breathes new life into the tradition, and uses the tradition to comment on the contemporary.

The plot is based on a power-play that interweaves the mythology of Yoruba and Ancient Greece. If, like me, you know nothing of Yoruba mythology – or, indeed, basketball – do not let that be a concern. The story-telling is clear and easily understood. Zeus fathers a son with Modupe, a mortal Nigerian. Their son, Demi, is as his name implies a demi-god. He is blessed with the power of gathering clouds and rainfall. He is also gifted with incredible basketball skills, metaphorically raining shots through the netting. While it is obvious that there is room for comedy here, this is unmistakably a tragedy, as Demi develops his hubris to his own detriment.

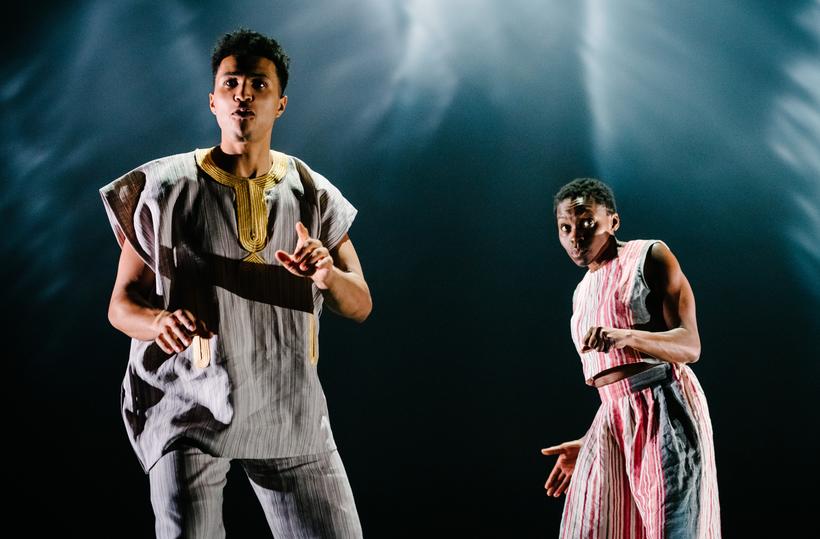

Should I call Ellams a poet or a playwright? This really did feel like an epic narrative in dramatic form, the monologues and dialogues were recitations of a crafted orality. The imagery, the pace and the prosody were all evidence of poetry. But whatever the distinction between playwright or poet, Ellams has created a work that is contemporary in its questioning of the ethics of tradition. The patriarchal dominance of Zeus is challenged, his parenting skills exposed, and the Son of Kronos is given a #MeToo treatment when Madoupe summonses the mythical help of Helen and Leda. Classical and contemporary references were mixed for sure, but nothing was too obscure or cliché, and it was all carefully crafted with the physical, aural and visual performance to maximise the drama of the narrative. Despite this, there was surprisingly little in terms of set. A circular black marble floor, a plain backdrop, simple but effective lighting and sound effects, and the most minimal of wardrobe support. None of this seemed to matter. The clarity of the narrative did not require more.

What the writing did require, however, were two strong performers. Both Rakie Ayola and Kwami Odoom fulfilled this requirement magnificently. Kwami used his physicality to great effect, particularly in the basketball scenes, and he was able to switch between personas with distinction and guile. In Aeschylus’s day the actors would have worn masks to help the audience keep track of the multiple characters, but the writing and acting abilities of Ayola and Odoom rendered masks unnecessary. Ayola’s performance was astonishing. I was utterly convinced from the moment she appeared, in whichever character she was playing. She was able to shift from the darkness of tragedy to the light of comedy and back again with fluency, and she held the audience engrossed. Her acting had a terrific intensity and has made a lasting impression.

The play lasted exactly ninety minutes. It played without an interval, and that was a good decision as it afforded the intensity to be maintained. Ninety minutes was just the right length for it. With only two actors and limited staging, I do not think the captivation would have held much longer for the modern audience. Nonetheless, it was captivating for that full hour-and-a-half, and well worth going to see if you want to re-engage with the epic tradition and experience some strong acting. ★★★★☆ Robert Gainer 17th April 2019