This Uncle Vanya is ravishing to look at, strikingly contemporary in its central theme, and frequently very moving. Ivan Voynitsky, ‘Uncle Vanya’, is a part that Rupert Everett had long wished to tackle, and he saw that the best way to achieve that ambition would be to direct the play himself. However, it would be very unjust to jump to the conclusion that his Uncle Vanya is some kind of vanity project. As adapted by David Hare, this is a version that sees the visionary Doctor Astrov as its most important character, not Vanya. Uncle Vanya is a play that challenges us to do something with our lives, and Astrov, alone of all the characters, is a doer.

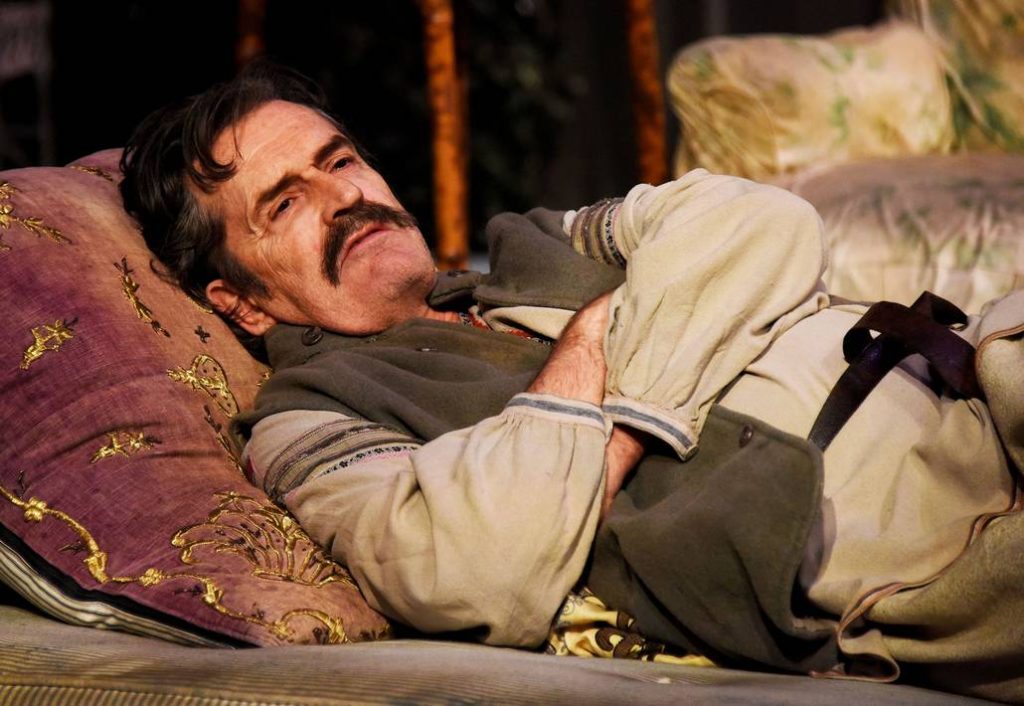

Conventionally, Vanya’s brooding obsession with lost opportunities and lost loves, his anger at a life wasted, is seen as the core of the play. Vanya has given his life to maintaining the country estate of his father-in-law, Serebryakov (Michael Byrne, on top irascible form), an academic that he once admired, but who he now sees as an exploitative charlatan. Everett plays Vanya like a great Russian circus bear, shambling back and forth in his cage, occasionally roaring out in frustration, but unable to escape. We see a cynical, vegetating misanthrope who has sunk into a kind of furious torpor. It is a magnetic performance, frighteningly volcanic one moment and darkly comic the next. Vanya’s impotence and inaction are vividly conveyed, but adapter David Hare has placed the centre of attention elsewhere. Turning from Vanya’s inert angst, he has instead focused upon a theme with great contemporary relevance, and in doing so he has created an Uncle Vanya that speaks vividly both of Russia’s sufferings in the late nineteenth century, and of the reckless damage we do to the natural environment today.

This places Mikhail Astrov (John Light) at the centre of things, for he is the one character whose impact upon the world is positive. Overworked and loathing the narrow provinciality of his life, he nevertheless cares for the countryside, and he cares for the future. His despair at the way his fellow men have destroyed the landscape, and his passion for tree planting are dismissed as bizarre eccentricities, but we see him as a prototype eco-warrior. John Light gives a subtle, multi-layered performance, showing Astrov as a man coldly unable to love or be loved, yet who comes alive when speaking passionately about the environment. ‘We demolish everything we can’t create!’ he cries. He shows the bemused Yelena, Serebryakov’s young wife, the maps he has drawn that reveal the inexorable march of deforestation. His interest is focused entirely on his drawings; she is interested solely in discovering his feelings towards Sonya, and they fail utterly to understand each other. Hare has generally succeeded in creating an Astrov who convinces as a nineteenth century environmentalist, though his line ‘The climate is changing!’ is perhaps jarringly more from our own time.

Katherine Parkinson, last seen on this stage in the splendid Home, I’m Darling, is a very touching Sonya, hopelessly in love with Astrov, and stoically accepting that if she is ever to find real happiness, she will find it in the next world, not this one. Supposedly plain, she sees both Vanya and Astrov fall under the spell cast by the beautiful Yelena. There is a poignant scene where Sonya finds herself alone with Yelena, and seeks to break the froideur that has grown between them. Clemence Poésy brings considerable depth to her portrayal of Yelena, a woman of intelligence and self-knowledge, yet one defined, even trapped, by her own beauty. She is certainly trapped in a loveless marriage. The two women bond through a mutual recognition of the tragi-comic nature of their circumstances, and they laugh and cry together.

Charles Quiggin’s very beautiful set, overhung with a cascade of leaves, blurs the boundary between the inside of the country house and the surrounding countryside. Later, the family sits outside, appearing tiny against an endless expanse of land that leads to a distant horizon, and we cannot tell where their property ends and the natural landscape begins. The trajectory of their lives is given external expression in the depiction of the seasons: there is sunlight, then thunder and rain; leaves fall, and finally there is snow.

Well supported by an exceptionally strong cast, Rupert Everett has created a memorable Uncle Vanya, both through his striking performance in the title role and more especially through his sensitive direction of David Hare’s skilful and sharply relevant adaptation. Highly recommended. ★★★★☆ Mike Whitton 30th July 2019

The production is transferring to the West End’s Harold Pinter Theatre in a new version by Conor McPherson opening on 20th January 2020.