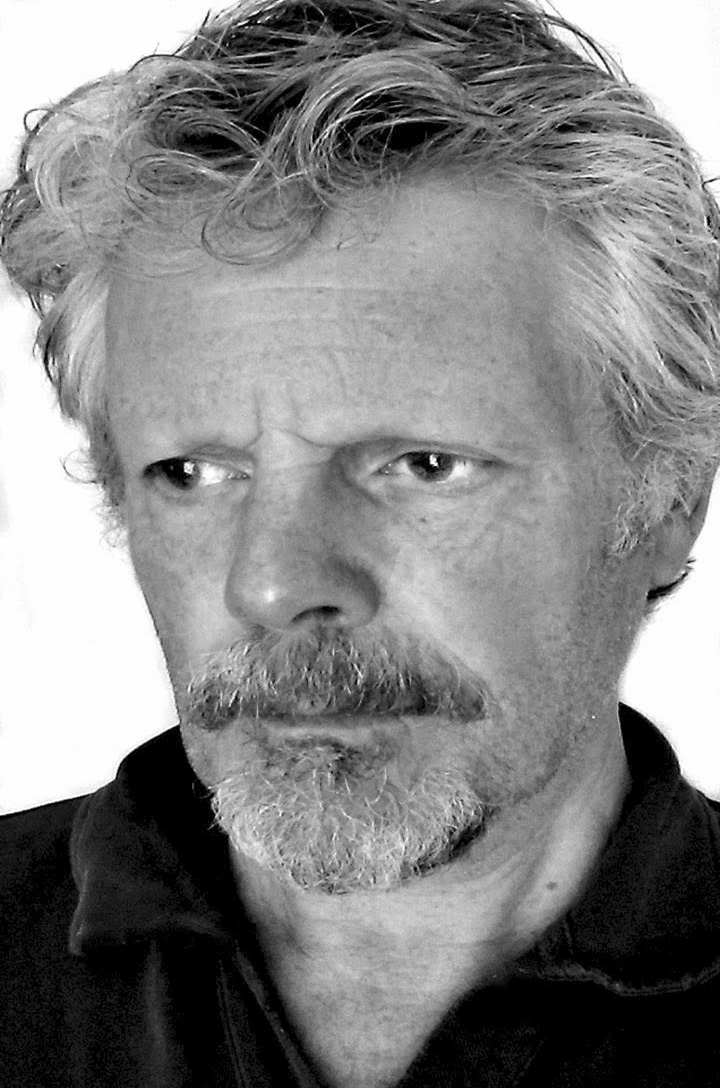

The thoughts of GRAHAM WYLES on the future of the theatre, post lockdown.

Whilst writing this in lockdown mode (standard fare for writers) and idly speculating when the curtains might rise again, I wondered what differences, if any, we might see on that happy day. I’m not particularly thinking of the practicalities, complicated though they are likely to be, but rather the content or tenor of new writing. The thought was prompted by that change in style and content, which followed The Restoration of the monarchy in1660 and the subsequent reopening of the theatres all of which had been dark thanks to the devout vandalism of the Puritans (aka England’s Taliban).

Whilst writing this in lockdown mode (standard fare for writers) and idly speculating when the curtains might rise again, I wondered what differences, if any, we might see on that happy day. I’m not particularly thinking of the practicalities, complicated though they are likely to be, but rather the content or tenor of new writing. The thought was prompted by that change in style and content, which followed The Restoration of the monarchy in1660 and the subsequent reopening of the theatres all of which had been dark thanks to the devout vandalism of the Puritans (aka England’s Taliban).

Whilst, thankfully, we are not about to come out of an eighteen year closure as was the case at the end of the 17th century other conditions chime in with our present situation: a deeply divided society – for roundheads and cavaliers read ‘leavers’ and ‘remainers’ – and a national crisis that threatened the fabric of the state – both national tragedies. Of course a few months (unlikely), maybe a year or two (perish the thought) is not exactly a generational interruption, but it does offer us the opportunity of taking stock, of standing for a moment and looking back over the landscape we’ve covered.

For many in the seventeenth century the Restoration occasioned a huge sigh of relief; an experiment in governance had run its course and the natural order was restored. New social types such as fops and rakes appeared as the Comedy of Manners allowed writers to both mock and examine the mores of the new order. Shakespeare’s mirror led to new understandings of who and what they were. Women, for the first time in our history, were accepted as fit to portray themselves even if only to exhibit qualities of sex and guile.

The whole world, let alone our own society, is currently in a state of flux, where it settles will be up to us. ‘These are my times and I must know them’, quoth the Roman poet Martial, a Spaniard, when chided by a friend for going to see lions devouring slaves in the Coliseum. Only by knowing the times can we hope to plot a way forward and the journey is much too important to leave to politicians alone. So the question is: what do we want to see on stage, what do we want our dramatists to be writing about and, importantly, that wouldn’t find an outlet in the mechanical media? To put it another way, what can the unique resources of theatre offer to the national debate as we stride into an uncertain future? What can theatre do to show the way to a better society, a better world? If we want (rightly in my view) our public spaces to better reflect the society we have become the same must be true of the arts, which, particularly in the case of theatre, uniquely straddle past, present and future.

The shifting tectonic plates of international politics at one end and the tensions and possibilities surrounding race and class at the other, bookend the realm of political theatre, the nuts and bolts of which are little changed since fourth century Greece. How do all the cogs fit together to provide opportunities for all to make a contribution? How do we seize the opportunity provided by the internet to make a global village whilst resisting a drift back into a cultural, ideological or geographical tribalism that is the Siren call of populism? How do we identify and deflate the new panjandrums?

Theatre does have the wherewithal to be light on its feet and it is certainly not short of the talent able to bring new work quickly to fruition, but how we do this under social distancing restrictions remains to be seen. Promenade theatre may offer a quick fix for some plays and open-air theatre may offer solutions to other problems, but one thing is certain; the theatre of the Restoration, notwithstanding it was an elite affair and not the mass entertainment of pre Commonwealth times was only possible with the support of the government of the day, which of course meant the patronage of the king. If today the government fails to step up and protect what has been built and developed over five centuries or more, the theatrical tradition could be reduced to a small number of favoured institutions patronised by a diminishingly small audience of diehards and curious tourists. Now that would be a tragedy. Graham Wyles 20th June 2020