29 – 30 March

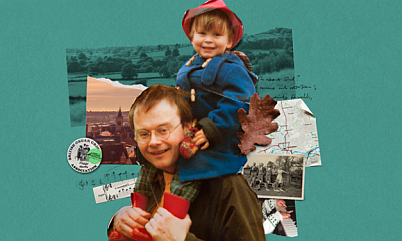

The roots of creativity and the father son relationship are potent subjects for theatre. But in this entertaining two hander, a collaboration between playwright Barney Norris and his father, the renowned musician David Owen Norris, the subjects are considered only superficially. The publicity leaflet promises an ‘intimate autobiographical exploration.’ Sadly, this promise is never realised. And despite the suggestive title, The Wellspring is tantalisingly brief in its study of the mystery of artistic inspiration. That said, this dual memoir, directed by Jude Christian, is never dull.

An upright piano has been placed downstage, a trailer parked upstage. The trailer is laden with household items including a chair, a rug, a small table, and a music stand. On a backlit screen, a rolling visual display depicts blurred home videos. These three stage areas form the setting for snippets of two personal histories, of which the father’s is the more engaging. David Owen Norris is a compelling pianist, composer and singer, and his extracts of Schubert, Brahms Elgar and others, are interwoven with lively stories of brutal instructors, terrifying competitions, and moments of sheer good luck. In addition to the superb playing, he has a natural easy presence with an audience which steals the show.

By contrast the onstage persona of the younger Norris is less assured. He seems to flounder with his bits of furniture and his cooking utensils, his references to his confused ambitions, his broken marriage. And while the lost young man is one of the themes of the piece, it never quite takes off; the narrative of the youthful graduate, moving between London rooms and basements is hardly original. Barney Norris is a likeable character, but it’s difficult to pinpoint what makes him special as a writer here, because so much of The Wellspring consists of transcribed conversations. There are striking set pieces, like the build up to his first appearance on stage, his terror before the production of his play and his experience of street violence. There are also memorable lines. ‘The weapon is less frightening than the look in a person’s eyes,’ he tells us. And he is wonderfully succinct in his description of the magic of performance. ‘It was all right for everyone to look at me. I became completely myself.’

The other theme is history and change. This is where the back projection becomes relevant. The audience is treated to wobbly, small scale, but delightfully evocative images of country picnics in fading colours. There are shots of the terrifying three lane trunk road that preceded the construction of the MI motorway. These are accompanied by sudden riffs from the father on the North South divide and the Watford Gap, as well as flashes of nostalgia from the son about playing a gig with his band at Stonehenge.

Beneath all these narratives flows the unspoken story of the separation of his parents when Barney was six years old. He describes walking up Blackdown Hill in Sussex at weekends when the family was together. Little is said of how that felt, but the lost connection is palpable. At one point his father says, ‘Your story sounds sadder than mine.’ And that short line hints at something deeper than this shared celebration of artistic achievement. It’s hard not to feel that ‘The Wellspring’ skates the surface of this father son relationship. Barney Norris is an award-winning playwright. The imagined world of fiction and drama may be a better place to express the psychological and emotional truth of his life than the supposedly realistic form of a two- handed memoir.

★★★☆☆ Ros Carne 30th March

Photo credit: Robert Day