23 June – 8 October

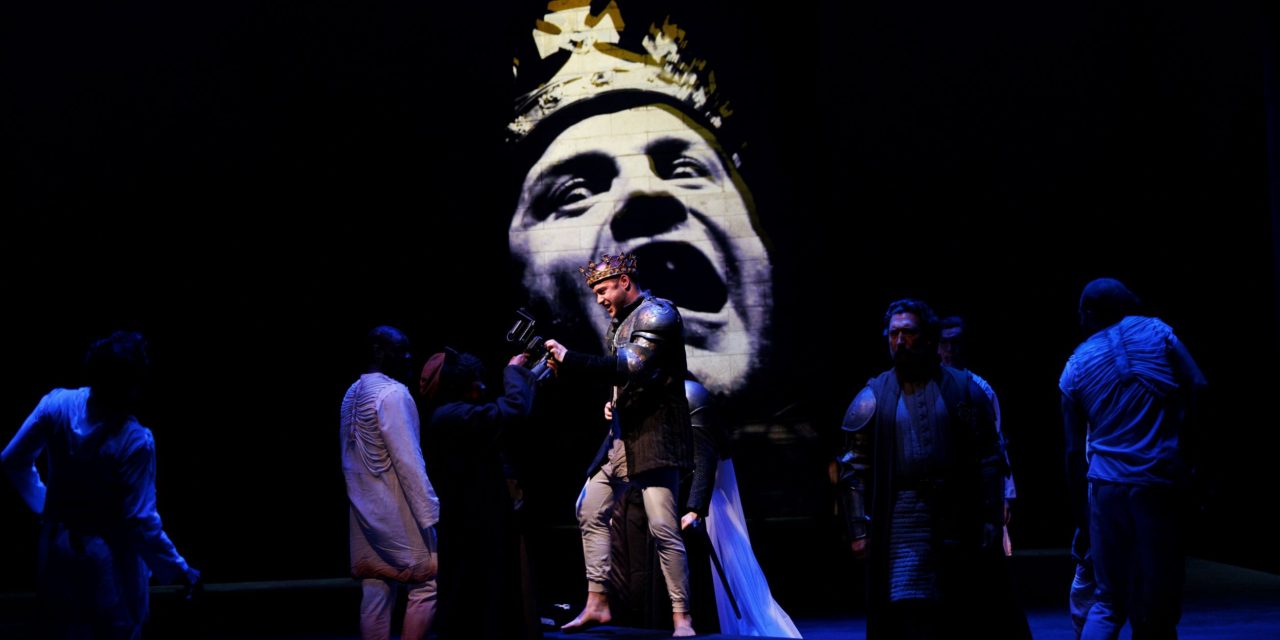

In one obvious sense there is no mystery about history – we know the outcome. In his history plays Shakespeare sets about showing how history works. It’s not a smooth road and particularly in Richard III it mocks the moral compass of society. Director, Gregory Doran has set his Richard in what we might call a neo-Elizabethan age. Designs by Stephen Brimson Lewis have more than an echo of Plantagenet sumptuary law about them and his spare set, dominated by a bleak and at times blood-washed cenotaph, place the scene in a post-war era with the constant looming symbol of pointless waste.

This is an angry production; the whole world seems to be angry. Richard himself is angry at his physical condition, angry at the world and society that spurns him. Nevertheless he is a product of his age. Arthur Hughes’ Richard is an outsider, but the same chance of nature that has afflicted him with deformity also gives him a position in society whereby people must, reluctantly, give him the time of day. Never have the words ‘My gracious lord’ seemed so hollow, so out of place; this Richard is neither gracious nor lordly. Nonetheless his malignancy is borne of bitterness. His opening speech is his one opportunity to gain our sympathy and he plays the card well. To his list of his ills and grievances he might well have added ‘unloved’. So he’s going to cause a bit of mischief, but oh dear, it’s really not his fault at all. And yet so inured are we to the misdeeds and duplicity of power, so commonplace has it become at the beginning of the 21st century that we do indeed now find it comical, even when taken to its egregious extreme.

Lady Margaret (Minnie Gale) is bottled, raw, incandescent anger. Her bitter jeremiads against Richard and the house of York are delivered as physical convulsions of hate, gobbets of bile ejected from an age-deformed body.

Mr Hughes has found his feet as an actor come his accession to the throne, he is more comfortable in his own skin having achieved his ambition, but now the unravelling begins. We might recall the words of Epicurus, ‘Nothing is enough for the man to whom enough is too little’, as, strutting and petulant he succumbs to paranoia. He is like a man who has won the lottery and proceeds to murder, unnecessarily, anyone who might want a piece of the action. Finally, devoid of all pretence of decorum he scuttles about the stage like an increasingly desperate performer trying to keep the plates from tumbling from their precarious and increasingly eccentric gyrations. From this point it can only end badly.

Mr Doran’s post war world of luxury and excess with which he opens the play seem to invite a reckoning. The attempt to manipulate emotions prior to the forthcoming showdown using video messages place us in the contemporary world of mass manipulation and its inherent dangers.

We may no longer have monarchs wielding power, but the message of this production is oh so relevant.

★★★★☆ Graham Wyles 1 July 2022

photo credit Ellie Kurttz c. RSC