HILTON ON THE TOBACCO FLOOR

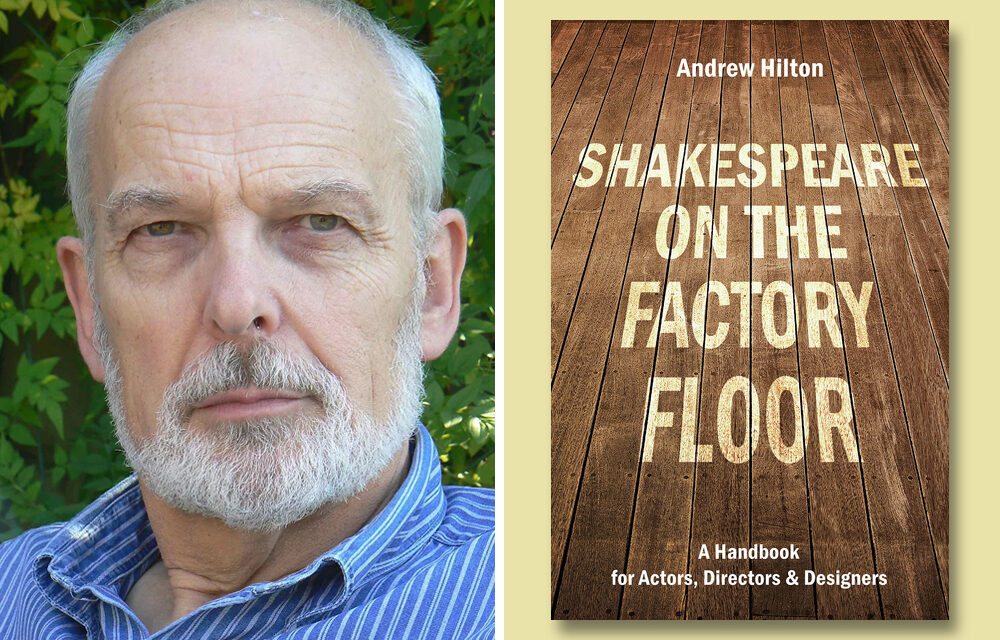

Something of a small miracle happened twenty two years ago when Andrew Hilton established a dedicated Shakespeare theatre company in an old Wills tobacco factory in Bristol. The miracle being that the enterprise worked, was a great success and became of major importance, attracting plaudits from audiences and the national press who would regularly make the trip from London to John Betjeman’s favourite city, travelling back on the last train. Performances for the London pilgrims would start half an hour earlier to accommodate the trek. Shakespeare was alive and kicking in the provinces and London based actors were eager to go west. Now, with the dedicated Shakespeare arm of the Tobacco Factory wound up (the theatre itself being still in rude health) and drawing on seventeen years of directing and producing Shakespeare (and a handful of assorted classics), Andrew Hilton has produced a book, Shakespeare on the Tobacco Floor, which draws upon his extensive experience.

StageTalkmagazine met him at home in Cornwall for a chat shortly after publication of the book. The intended audience is, unabashedly, anyone interested in theatre, but with an obvious bias towards the Bard. He writes with a willingness to pass on his experience to others involved with theatre; actors, designers and directors. It’s the kind of book Stanislavski would have approved of since Hilton is at great pains to examine the diversity and richness of motivation in Shakespeare’s characters, which he does and does so with an acute eye and ear and in exhaustive depth.

Anyone not familiar with the rehearsal process in a professional theatre company will find in the book an enlightening corrective to any such dismissive idea as that, ‘actors just learn the lines and go on’. No, here they will find characters are laid on the psychiatrist’s couch and interrogated at length with humanity and humour. I was surprised then, given his initial analytical stance, that his approach is not as formulaic or regimented as one might expect. For example, we might well understand that the rehearsal process is a time of exploration to be approached with an open mind; Hilton cautions against actors going into an audition assuming the director knows what they want. It is however, for him at least, an opportunity to see how the actor ‘responds to the language’, is the actor, ‘alive to the language, do they allow it to shine, are they light with the pentameter?’ Again, of auditions he advises, ‘It’s not a competition for being good at acting – just a role’. And he remembers the unnamed actor who auditioned dreadfully for him in his very early days as a director at the Mermaid but was cast as there seemed to be no-one else. He turned out to be terrific in that show and deservedly went on to become a leading classical actor.

In discussing the nuances of language and interpretation he stresses the importance of ‘beginnings’ to set the theme and tone of the play. The opening of King Lear, for example, could be seen as a formal yet joyous occasion with something like a party atmosphere where the prenuptial agreement of Cordelia’s betrothal to the king of France is being announced along with the old king unburdening himself of his royal duties. At the same time the three daughters would be excited at the advance in status that will flow from momentous constitutional changes. And of course these events have an emotional impact, which marks the start of the characters’ journeys in the play. Similarly the way in which Lady Macbeth first greets her husband will set the trajectory of their relationship, be she excited, cautious, concerned or whatever.

In conversation he’s clear about his respect for Shakespeare’s text/s and although quite happy to adjust the chronological setting is nonetheless chary about productions which see the plays as, ‘A marketable vehicle for directors’ ideas’. Done properly (my words) Shakespeare needs no lengthy introduction by way of programme notes, ‘Audiences understand at a subconscious level.’ Shakespeare’s understanding of how people behave is unsurpassed, ‘We don’t know more now than Shakespeare did. We have to stretch our imagination to keep up with him.’

I suggested his book revealed a preference for Shakespeare’s ‘problem’ plays, a thought he agreed with, ‘But I’ve had more success with the comedies’ he added wryly, ‘The Two Gentlemen, All’s Well, the Dream’. His Titus, which played to only 40% audiences led necessarily to an appeal to save the company, ‘That was a learning experience in producing Shakespeare in the theatre’. (ST) ‘Are there any you’d like to do again?’ (AH) ‘Well there’s a feeling you can never quite get it right, you’re trying to make good choices all the time. We need to constantly interrogate our own preconceptions’.

With his love of Shakespeare undimmed after all the stresses of running a professional theatre company Andrew Hilton will continue to teach and hold Shakespeare workshops (details are on his website and also on the University of Bristol: Interpreting Shakespeare). The book is out now under the imprint of Nick Hern Books and available from bookshops or to order.

Graham Wyles, October 2022

Photo credit: Alan Coveney