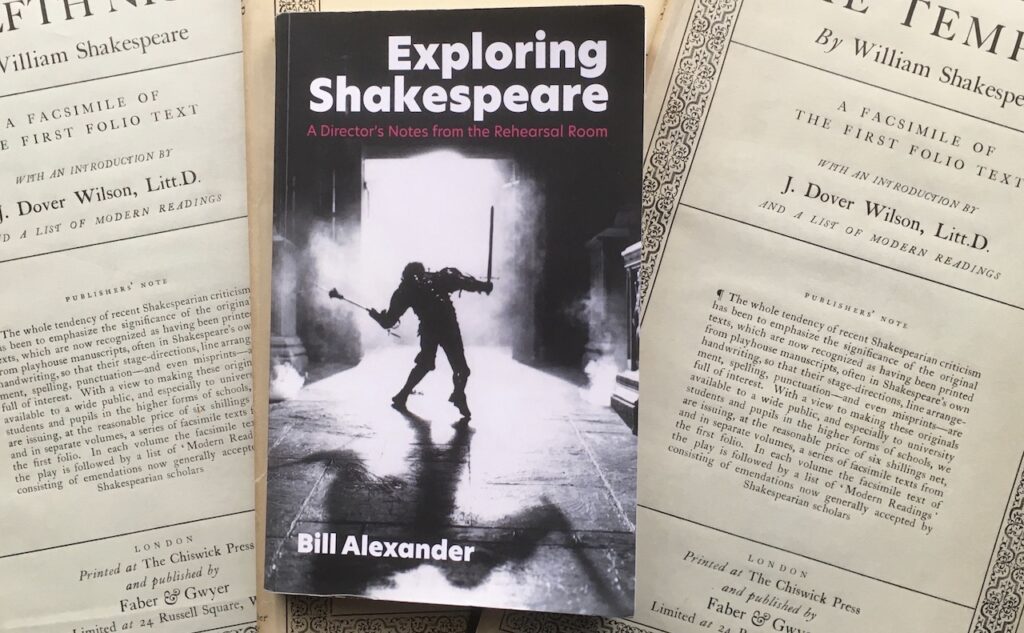

Exploring Shakespeare A Director’s Notes from the Rehearsal Room by Bill Alexander (Nick Hern Books 2023}

Review by Andrew Hilton, August 2023

Bill Alexander directed for the Royal Shakespeare Company from 1977 to 1992, his many productions there including the famous Richard III with Antony Sher, and a Merry Wives of Windsor that won him the Olivier Award for Best Director in 1986. He had previously directed for the Bristol Old Vic and the Royal Court. After leaving the RSC he became Artistic Director of the Birmingham Rep where he continued to direct Shakespeare alongside other classics and new work. Since 2000 he has worked freelance, including more Shakespeare for the RSC.

In Exploring Shakespeare he offers first a series of short essays on such important subjects as the arrangement and conduct of the rehearsal room, the choice and editing of texts, the blurred line between comedy and tragedy, the absence of subtext in Shakespeare, the usefulness of the backstories suggested by lines such as Lady Macbeth’s “I have given suck”, the crucial relationship between character and narrative, and the particular nature of soliloquy. In all these he is insistent that the director’s role – and this is essentially a book for directors – is to help the actor ‘find the way to be human’. The actor – the ‘centre’ and the ‘soul of theatre’ – must be the focus; their courage in putting themselves at risk on the stage must be recognised and cherished and the context – created by director and designer – in which their characters take life, must serve their art.

He goes on to longer essays on eight plays – Titus Andronicus, The Taming of the Shrew, The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, Twelfth Night, Othello, King Lear and The Tempest. All these deserve close attention, for he is always rigorous and sometimes challenging. He has certainly made this writer think more positively of the ‘casket scenes’ in The Merchant of Venice, for which he supplies a convincing rationale. And although we approach important aspects of Hamlet very differently – he makes more of Hamlet feigning madness than I would myself – he writes particularly well of the play’s contentious religious background and of Ophelia, of her position in the society of 1600, of her vulnerability, her want of the tools to refute her brother’s and father’s fearful certainties, and of her breakdown into madness.

In this, and everywhere, he is insistent that a production must accord a world to a play, one in which social relations and hierarchies make sense. In the chapter on Twelfth Night, which is perhaps the most telling of all (he has directed the play five times), he explores the social realities of the time, with particular reference to Malvolio, so often mistakenly imagined as a mere butler. His place in the shifting hierarchy of wealth and power must be clearly understood, as must his world’s sexual mores. The idea that a young woman of Olivia’s status could sleep with a young man prior to their marriage is unthinkable in the Elizabethan context; her hurried wedding to Sebastian is therefore driven by urgent emotional need, not by mere whim in obedience to a fanciful plot. Though this could lead Alexander to dismiss the modern contexts now so often favoured, he is reluctant to do so, and has indeed explored them himself (his award-winning Merry Wives was set in the 1950s). But throughout the book he is concerned to inhabit the Elizabethan mind. If a modern setting is chosen, how do we ‘make the audience believe that characters who look like us can think like Elizabethans’? Repeatedly he poses the question. Plausible solutions may, or may not, be found.

Everywhere the detail mounts up: there are eight pages on the brief dialogue between Viola and the Sea Captain in Twelfth Night’s second scene. But this is the point; the director’s job – and the actors’ too – is to interrogate the script as minutely and as openly as possible, never to arrive at the play with preconceived intent, seeking only confirmation.

Everywhere the questioning is thorough and scrupulous, and always aimed at the clearest articulation of Shakespeare’s purpose and the most vivid realisation of character-driven narrative.

This book is no mere accumulation of ‘notes’ from the rehearsal room floor, but a primer for the Shakespeare director, packed full of wisdom, pithily expressed. Directors who are determined to prioritise their own imagination over Shakespeare’s are unlikely to read it, even less likely to learn from it if they do, but it should be required reading at any institution that pretends to teach the difficult art of direction. It is a fine achievement – a necessary and timely one – and I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Andrew Hilton directed Shakespeare at the Tobacco Factory from 1999 to 2017