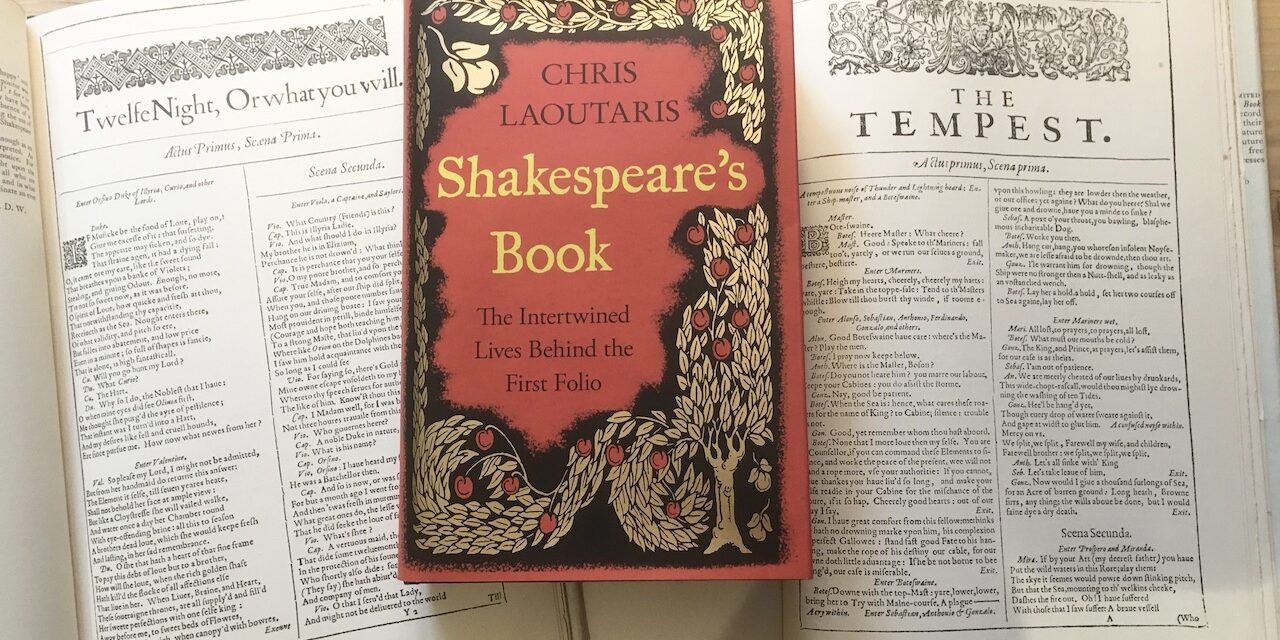

‘Shakespeare’s Book: The Intertwined Lives Behind the First Folio’ by Chris Laoutaris

William Collins 2023

Reviewed by Andrew Hilton

In this 1st Folio Quatercentenary year, it is appropriate that we should be offered an account of that great book’s provenance and publication, and here Chris Laoutaris provides an exhaustive and meticulously researched one. Though lucidly, even elegantly written, it is not a page-turner, or a candidate for a very large Christmas stocking, but a seriously academic work for the serious student market.

Shakespeare and Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre obsessives – of which I am one – long for human insights into the leading figures of the time; into Shakespeare himself, his leading actor, Richard Burbage, his collaborators and editors, Henry Condell and Richard Heminges, and a host of others – their fellow actors, their playwrights and their audiences; we long for their letters, their conversations, their affairs, their working practices, their tastes, their jealousies and secrets, their gossip; but such material is rare indeed. What we do have is records of financial and legal events – property transactions, loans and debts, disputes in court (and sometimes criminal prosecutions), licences for play publication, playhouse accounts, birth, marriage and death records and – of course – wills.

All these, together with contemporary political events (not least the long protracted, and controversial proposal that crown prince Charles’ should marry the King of Spain’s daughter), Laoutaris has mined to provide a complex picture of the years leading up to the Folio publication in 1623, an event that so easily could not have happened. That would have been at a cost to posterity of eighteen of the plays, including Antony & Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, The Tempest, Twelfth Night and The Winter’s Tale, none of which had appeared – or have survived – in single, Quarto editions.

We are disabused of any notion that all Heminges and Condell had to do was to reach into the stage management cupboard at the Globe for the pile of prompt copies and hand them over to their chosen printers, Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount. The Globe had retained some of the plays, but the ownership of others was divided between up to a dozen booksellers, stationers and other rights holders. Here we are reminded that authors’ copyright did not exist as we know it today; plays were owned initially by the theatre companies for which they were written, who could hold on to them, or sell them for publication, or as assets. When the Folio project was underway it is believed that a number of these valuable properties were discovered to have been stolen.

So lengthy searches had to be undertaken (which may have taken Heminges and Condell to Stratford to consult the elderly Anne Shakespeare – she was to die months before publication) and deals to be negotiated. A syndicate was formed and sponsors acquired. The costs of the whole print run, supposed to be of 750, were huge. The paper alone, Loutaris estimates, would have cost in today’s money £11,000, and the total cost in the region of £33,000.

How far back the plan reached is uncertain; we shall never know if Shakespeare himself had hoped for it, or given the germ of the idea his blessing before his death in 1616. It seems likely, however, that it was lent impetus by the death of the King’s Men’s leading actor, Richard Burbage, in March 1619. He had towered over the London theatre scene and his death was met with an extraordinary outpouring of grief across the city, occasioning a reminder of the great roles Shakespeare’s had written for him – among others Romeo, Lear, Hamlet, Richard of Gloucester, Macbeth and Othello, as well as Marlowe’s Edward II and Jonson’s Volpone.

The task was formidable; apart from the acquisition of rights and the funding challenge, the editors had to choose between versions of the texts, always remembering that stage practice over several decades, various quarto printings, interventions by the censor, and sometimes the work of other hands than Shakespeare’s own, may have impacted for good or ill on his original intentions. They also had to decide on the sequence – the categories, ‘Comedies, Histories and Tragedies’ are their own – and here Laoutaris speculates interestingly on the choice of The Tempest to begin the volume: was Prospero Shakespeare’s own last performance for the King’s Men, and so celebrated in this way?

All these matters are reviewed in detail, as is the physical process of bringing the Folio into being. There is an evocative and detailed picture of the scene within the Jaggards’ printing shop – the racket and the smell, the compositors’ practices, challenges and errors – when the Folio finally went to press. It was to take two years to complete, all the while Heminges and Condell producing new plays, and the Jaggards taking other commissions. The first recorded sale of the volume was on the 5th of December 1623, to an Edward Dering, who bought two copies for £2.

Shakespeare’s Book is both detailed and wide-ranging; also beautifully illustrated. Subtitled The Intertwined Lives Behind the First Folio the web of connections it reveals within and beyond the group of syndicalists, editors, and printers cannot be divorced from the urgent events of the day or the principal players in them; and so Laoutaris’ research will be of interest to historians of the period as well as to bibliophiles and Shakespeare enthusiasts. If that sounds a little dry, then I must add that he gets closer to the street in Jacobean London than I have found elsewhere, particularly to the booksellers’ and stationers’ streets in the shadow of St Paul’s, where he acts as the most authoritative and expressive guide.

And what of Richard Heminges and Henry Condell? Our debt to them is incalculable, and yet they are rarely celebrated. Their editorship – rather than just management – of the Folio plays has been questioned, with the Oxford-educated John Florio, now known chiefly for his Elizabethan translations of Montaigne and Boccacio, proposed in their place. Happily, Laoutaris makes no mention of this very questionable hypothesis.

And why weren’t Heminges and Condell up to the job? Because they were actors! Some prejudices never die.

Please drink a toast to Richard and Henry over Christmas!

Andrew Hilton, formerly the Founder & Artistic Director of Shakespeare at the Tobacco Factory, is the author of ‘Shakespeare on the Factory Floor’ (Nick Hern Books 2022)