29 January – 10 February

One of the things we have learned about the Ustinov under the stewardship of Deborah Warner is the capacity of a small space to bring intimacy to both large themes and small. For the performer – actor, singer or dancer – there is no hiding place. Everything becomes significant to an audience accustomed to look for significance. After all, that is the difference between a created work and a slice of life. We go to our theatres for that very thing and we do it as a group.

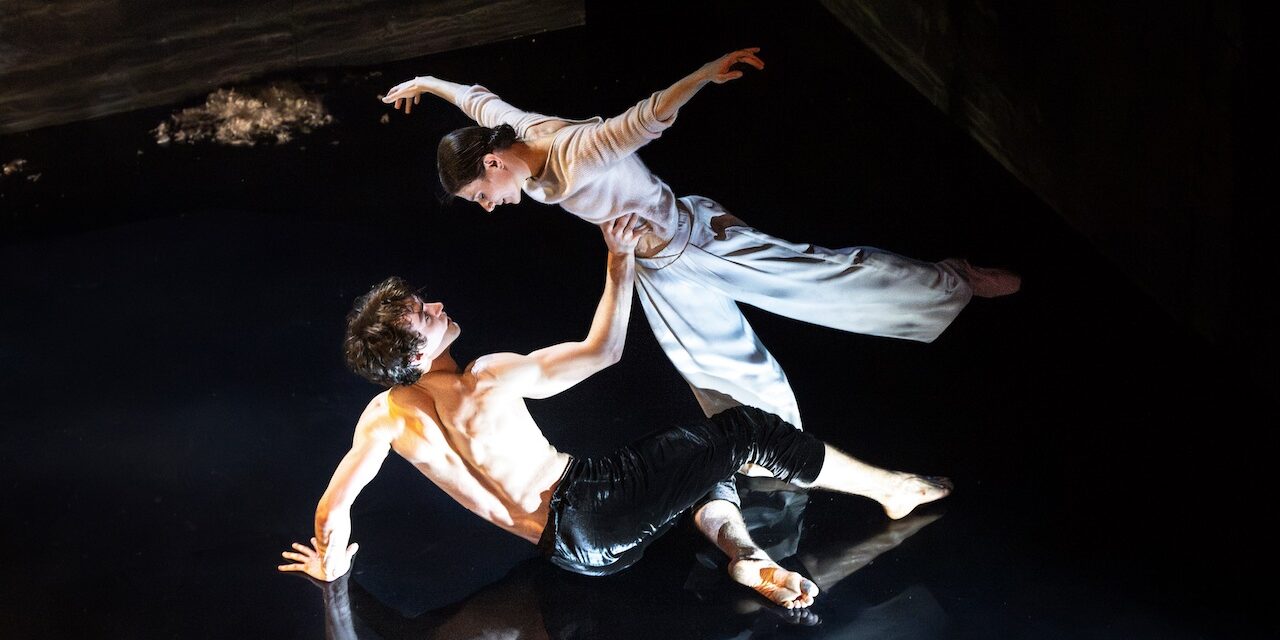

In Minotaur the labyrinth is the prison of the Minotaur, a monster, half man half bull, who is the fruit of an act of bestiality between Ariadne’s mother and a bull. Ariadne (Kristen Mcnally) who has been given the task of guarding the labyrinth, in helping Theseus to kill the Minotaur thus carries both the guilt of her mother’s deviancy and a hand in killing her half-brother. Kim Brandstrup gives us an Ariadne who is thus complex in her relationship with Theseus. The dance between them is therefore full of contradictions; ebb and flow as attraction and guilt. Arms form both arcs of embrace and barriers, ecstasy and doubt pulsate through her movements. Theseus (Matthew Ball), nothing loath, sweeps the girl off her feet.

Justin Nardella’s spare, black box of a set includes a climbing wall enabling the notion of being a fly on the wall to be given substance by Tommy Franzen who as Dionysus falls in love with the abandoned Ariadne, she having been deserted by Theseus. To do a handstand on the side of a wall takes not merely skill, but balls. His emergence, Deus ex machina, to carry out the seduction of Ariadne is consequently not only artistically satisfying but also carries the frisson of danger.

The sound design of Eilon Morris gives us the atmospheric sounds of a cave and a variety of moods, from ancient sounding strings and wind to a dark and plangent piano.

The second part of the double bill, Metamorphoses, examines the notion that the person of one’s dreams can only be that when never exposed to the light of day. The characters are operating in the dark, their senses of touch thus heightened. Cupid and Psyche (Alina Cojocaru and Matthew Ball) live out a kind adolescent fantasy of perfect harmony in which Cupid can avoid commitment to the real Psyche with all the imperfections that naturally attend a human. Until Psyche reveals her true self they love and live in a world of pure and ultimately unsustainable sensuality.

Both pieces are sensual and articulate whilst giving the audience the privilege of being in the same room as consummate artists.

★★★★★ Graham Wyles, 2nd February 2024

Photo credit: Foteini Christofilopoulou