10 April

When Igor Stravinsky saw Hogarth’s famous series of paintings in 1947 he immediately conceived of them as scenes for the opera he longed to write. His California neighbour, Aldous Huxley, suggested WH Auden as a librettist, and a great artistic partnership was born. ‘He was inspired, and he inspired me,’ said Auden who loved opera and was happy to tailor his language to Stravinsky’s compositional needs. The result was, and is, a brilliant tapestry of word and sound.

The Rake’s Progress feels surprisingly melodic for a mid-20th century work and, with its recitatives, arias and choruses, has been described as ‘neo classical’. It employs a harpsichord continuo and owes much to Mozart, musically and dramatically, in particularly to Don Giovanni, with its focus on sensual excess and retribution. At the same time, it is unmistakably Stravinsky, with his inimitable energy, rapid mood shifts, expansive emotional range and restless ambiguity.

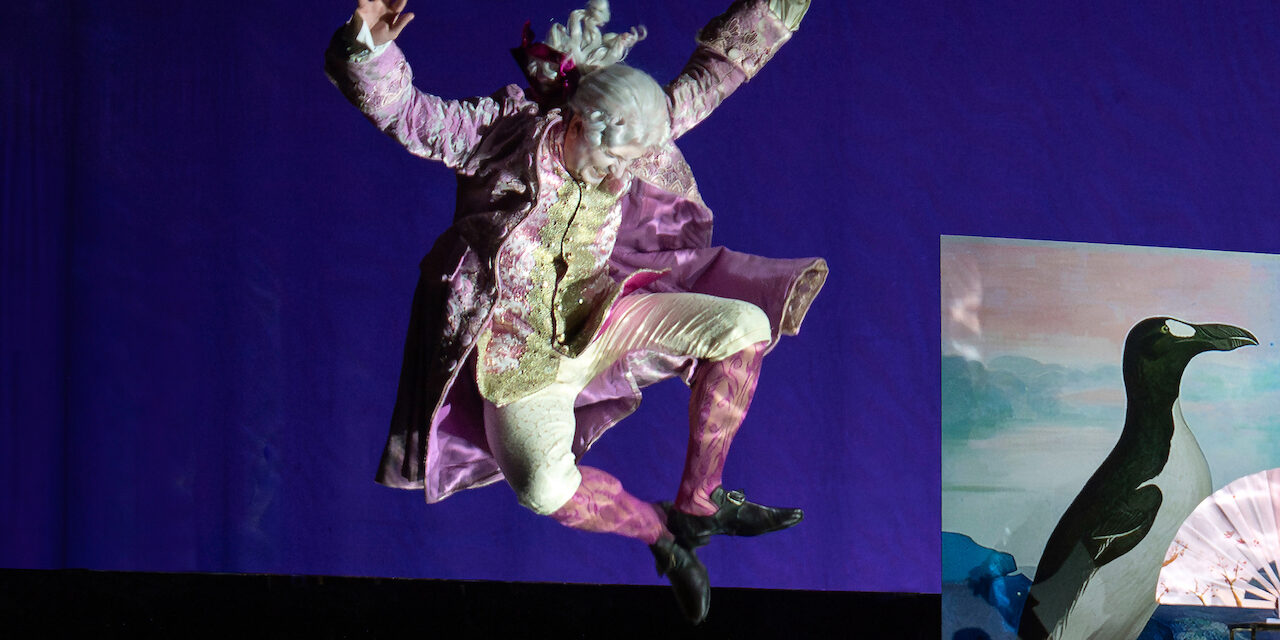

The current production by English Touring Opera, is colourful, fast-moving and exuberant. Director Polly Graham describes it as an opera of ‘dazzling surfaces,’ and, through her collaboration with designer April Dalton, she provides a sense that, like the hero Tom Rakewell, we are observing a series of dreams and phantasmagoria, where nothing is quite what it seems. At the outset, as a backdrop to the rural idyll, members of the chorus are costumed and masked as macabre creatures from the Venice carnival. Their slow balletic motions around a maypole, giving more than a hint of foreboding.

But while the sense of macabre arrives early on, Nick Shadow himself, the Devil in disguise, appears almost jovial by comparison. Jerome Knox is a pleasure to watch and listen to with his silken tones and charming smiles. But he exhibits few of the usual diabolic traits and some Stravinsky afficionados might wish for a more sinister rendering.

As for the two principals, both excel. Frederick Jones has not only the voice but also the acting skills required for the taxing part of Tom Rakewell. He is equally at home with swagger and with lyricism, while managing to move like an athlete. His counterpart, the pure Anne Trulove (Nazan Fikret) is easily his vocal match, holding back a little at first but growing in confidence as the role demands, soaring to an effortless top C in the great aria that closes Act One. She sings it on an empty stage, against a dark backdrop and a full moon; a wonderful moment of stillness and beauty.

The only problem with this couple is that one might hope for more sense of her pull on him. And though her desperation is palpable, the final farewell in Bedlam feels a little cursory.

This is a hugely difficult opera to stage with its rapidly developing plot and sudden changes of scene and mood. Here the chorus is an almost constant presence switching seamlessly between country dancers, inhabitants of a brothel, buyers at an auction and occupants of Bedlam, providing the visual and dramatic envelope to the whirling narrative. There are, however, moments when the stage feels a little over-full. It’s almost as if we have hit Bedlam before we get there.

The ensemble is ably led by conductor Jack Sheen. His enthusiasm never falters and the multi-layered score offers the opportunity for all the players to shine. This is true in more than one sense, as a mirror at the base of an onstage platform reflects the orchestra from the Playhouse’s pit.

With its layers of musical and verbal complexity Stravinsky asks a great deal of his cast. And these young performers sing their hearts out in what must be gruelling tour of sixteen English cities in three months. Quibbles aside, this is certainly a production worth seeing.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith