16 – 25 January

Directed by Jonathan Church, this fine production of Robert Bolt’s A Man For All Seasons stars Martin Shaw as the intransigent Thomas More, refusing to bow to pressure to assent to Henry VIII’s annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Shaw first took to the stage as Thomas More twenty years ago, and the role fits him like a glove. He vividly conveys More’s high intellect, moral certitude and deep religious faith. However, in the dangerous times in which he lived, it was not always wise to make one’s beliefs known and More is often seen refusing to be explicit: ‘I trust I make myself obscure.’ He believes his silence on the rights or wrongs of Henry’s divorce will protect him under law. In that he is wrong, for there are other powerful men less concerned with moral and religious scruples and more focused upon political expediency. They will find a way to destroy him.

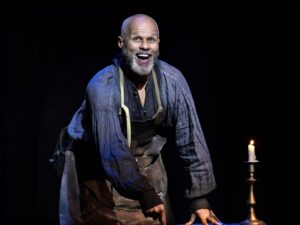

Gary Wilmot is brilliantly cast as The Common Man. With a few simple on-stage changes of costume he becomes More’s servant, a publican, a boatman, More’s jailer, the foreman of the jury at his trial and, finally, his executioner.

Cheerfully cynical, and always ready to persuade his customers to give him a generous tip, Wilmot’s engaging performance is one of this production’s greatest strengths. His Common Man represents the down-to-earth pragmatism with which most people cope with life’s vicissitudes

Down-to-earth pragmatism is also seen in the machinations of Thomas Cromwell, played with brisk, cold directness by Edward Bennett. In Bolt’s play we see do not see a nuanced, complex version of Cromwell familiar to viewers of Wolf Hall. Here he is simply the ruthless instrument of Henry’s will, prepared to use any means to achieve his ends.

As for Henry himself, in the first act we see him make a supposedly chance visit to the More household where he jovially assures his Lord High Chancellor of his friendship, while making it very clear that, whatever his private views, he expects More to be utterly loyal in public. As Henry, Orlando James very effectively portrays Henry’s glamour, his vanity, his mercurial temperament and his absolute conviction that he must have a male heir.

Is all this history? Yes, but only up to a point. Bolt has tidied up some of the facts, we get a cleaned-up Thomas More in what is very nearly a hagiography. The real Thomas More could be every bit as ruthlessly cruel as Thomas Cromwell, happily sending Protestant reformers to burn at the stake and with views about reformers such as Luther and Tyndale that were often expressed in obscene and violent language.

The most moving scene in the play comes when we see More being visited by his family after a year in prison. They are desperate for him to sign the Oath of Supremacy and save his life, while he, desperate to change the subject, praises the food that his wife has cooked for him. Shaw vividly conveys a man agonised by the choice he believes he must make for the sake of his soul, even if it is at the expense of the happiness of those he loves most. His righteousness is admirable and infuriating by turns.

This A Man For All Seasons acts as a timely reminder, if one is needed, of the importance of morality in political life. Fortunately for those of our politicians who have moral principles, there is no risk of a visit to the executioner’s block.

★★★★☆ Mike Whitton, 23 January 2025

Photo credit: Simon Annand