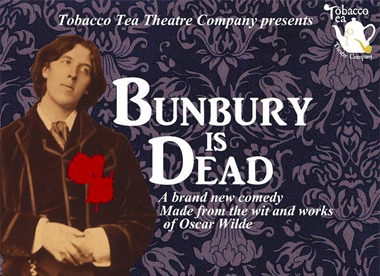

In devising Bunbury is Dead, Christopher Cutting has come up with a wonderful idea. After all, if a good line is worth using once, why not use it twice (as Oscar Wilde definitely wouldn’t have said)? His (Cutting’s) play has been fashioned from words gleaned from the theatrical works of said playwright and author. From this familiar and entertaining material has been fashioned a tale of such beastliness, such cunning and dastardly intent.

With its lineage one can be little surprised at the blizzard of maxims, epigrams and aphorisms with which the cast beat the audience from the outset. Loosely draped over a story of unrequited love, languor and naked ambition Cutting has seamlessly woven his Wildean script. The eponymous Bunbury (George Mills) lies (literally and metaphorically) in his bed, whilst creditors are kept at bay by the resourceful butler, Douglas (Calum Anderson). The pretence of unspeakable and un-diagnosable illness is also used to pre-empt the matrimonial machinations of formidable aunt, Lady Worthing (Rebecca Haselhurst) who is determined that Bunbury should become engaged to the charmingly coquettish and financially well endowed, Constance (Jasmine Atkins-smart).

Meanwhile, Bunbury’s best chum, Rupert (Peter Baker), an over-sensitive and unfashionably intellectual artist, has fallen hopelessly in love with the object of Lady Worthing’s scheming, but is rejected in his advances and protestations of love by a Constance whose affections have been attached to the outwardly attractive and intellectually superficial Bunbury – ‘Beauty ends where intellectuality begins’. Unfortunately for Constance, Bunbury does not reciprocate this particular set of superficial emotions. The romantic impasse is resolved by a dark stratagem cooked up by most un-Jeevesean, Douglas – which I will not spoil by revelation here.

One thing the play does highlight is just how much the Wildean dialogue tends towards superficial, the morally ambiguous and is pretty much interchangeable plot for plot. The danger for users of such richly gnomic dialogue is that each line is given equal weight such that when a real belter of a line comes along it does not stand out from the rest, which are all sold by the actors as being of equal worth. The gems get lost amongst the cut glass.

Tobacco Tea Theatre Company have set themselves up as exponents of the Comedy of Manners, both old and new and on this showing have set off, best foot forward. With a little more attention to variation, being a little lighter here, more conversational there and with a nod to the precept that in the Comedy of Manners ‘style is everything’, this show has all the makings of a winner. ★★★☆☆ Graham Wyles