David Lane’s play takes the form of a first person, present tense narration of the descent towards psychological collapse of a complex and troubled personality. In lesser hands the fact-into-conceit of this subject might have produced little more than a depressingly parochial chronology-cum-travelogue, but the direction Lane has taken gives us a credible exploration of an area of personal (and to a lesser extent social) identity as it affects a damaged personality. The bald facts of Svetlana Alliluyeva’s life are a matter of record; the defection, the marriages, the time in America and the subsequent British citizenship. For the writer however, these can never be anything more than a skeleton upon which to flesh more intractable and interesting concerns.

The mild paranoia resulting from the effects of multiple identity as – the now Phyllis Richards – attempts to escape both the legacy of a father who stands as one of the twentieth century’s great monsters and the sclerotic system he developed have given Lane his starting point.

Unable to relate in any meaningful way to her new environment or the people in it, personified by greengrocer, Vince and permanently engulfed in the mephitic cloud of her father’s pervasive legacy, which penetrates her very being, Phyllis goes slowly bonkers. It’s a convincing if not entirely satisfying portrait which given the one act, one set, one actress constraints of the production is as much as director and performer could squeeze out of the script.

Director, Ed Viney, has kept attention focused on the inner life of Svetlana/Phyllis so that, for example, we are never quite sure if her companion, ‘Lelka’ (I think) is real or imaginary. The trajectory he has taken is paced, but for that no less dramatic. The changes of time and location as Phyllis recalls (or has psychotic episodes involving) her past are adroitly handled and never jar.

Kirsty Cox gives a magnificent performance as the defector, troubled and haunted by a past, which gnaws away at her equilibrium. It is a performance, which from the outset is taut with nervous energy and never fails to engage our sympathy as she tries to assume a new identity with which to cloak her past, a past which refuses to be erased from the memory. There is a certain earnestness and eagerness with which she relates her history and predicament and a subtle bafflement at her new cultural situation.

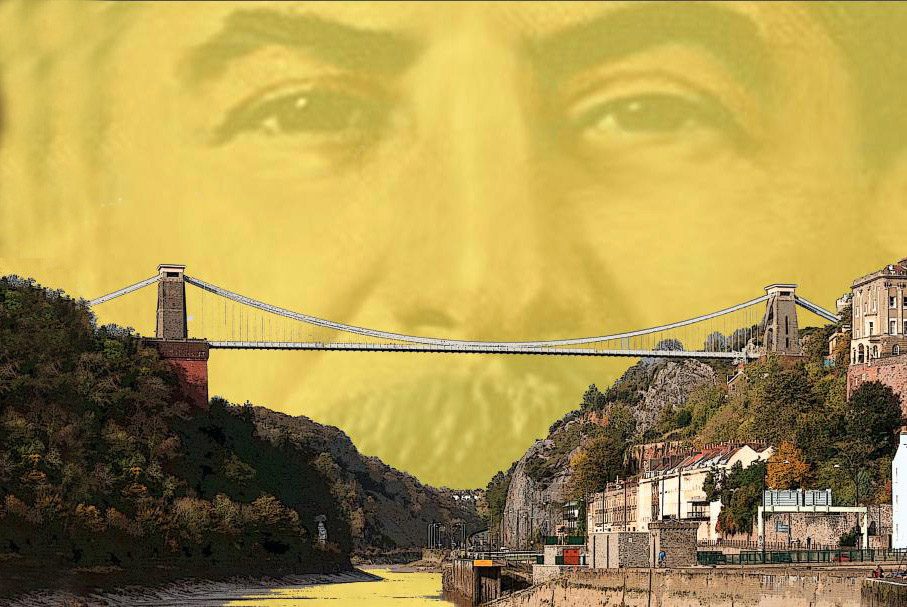

James Helps’ slightly expressionistic set adds to the feeling of disorientation whilst the lighting design of Ellen Abraham-Williams suggests enough movement between inner and outer, past and present. ★★★☆☆ Graham Wyles