We live in a solipsistic world. That’s one good reason why the arts and in particular theatre arts are so important. Seeing the world through another’s eyes or more precisely through another’s consciousness gives us a new perspective on the world and forms the basis of our morality.

In Christopher Hampton’s translation of Florian Zeller’s play we are like homunculi peering out through the consciousness of a dementia sufferer, seeing their world as a perplexing reality. It’s not that Kenneth Cranham’s character, André, has lost his marbles, rather that they are somewhat jumbled up. The ‘reality’ we share with him is vivid and therein lies the difficulty for the character and in quite another way for the audience as well. But for us the difficulty is a pleasant one as we puzzle over what is before us: is the character being tricked, is André being set up for a scam, are we watching an alternative reality or some kind of play with time?

With a grim symmetry, as it becomes clear to the audience that we are witnessing a slow decline in mental capacity so life becomes more confusing for the character of André. Navigating his way around his own mind becomes a continual challenge. In this state what to him is a perfectly normal response to a situation is, to those around him, progressively disturbing. As his daughter, Anne, says, he is quite ‘capable of acting unexpectedly’. In this state tolerance and compassion are tested to the limit and the dark shadow of abuse appears, albeit fleetingly.

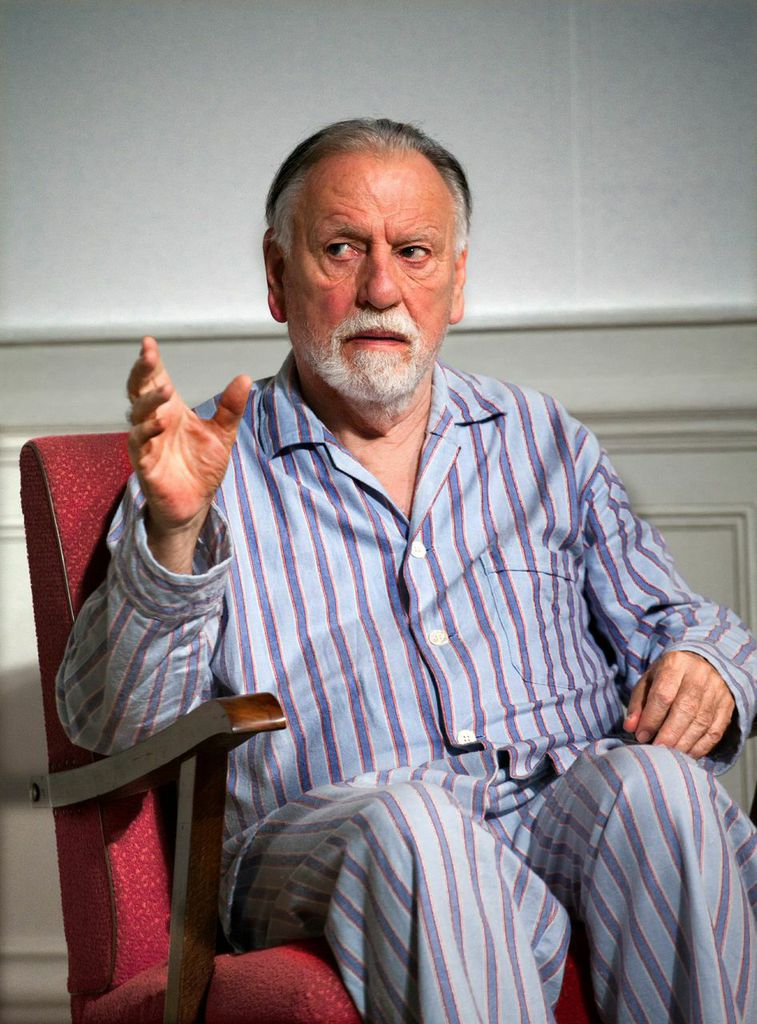

This is a fine play, which in Kenneth Cranham, is matched by a performance of great stature – like a late Rembrandt self-portrait: detailed, revealing, unabashed, honest. The acting is controlled, full of insight, of variations of light and shade, a performance of true pathos, which never sinks into or reaches for the crutch of maudlin sentimentality. To the final, wrenching, reversal of the roles of father/daughter and the ultimately unbearable last plea in the arms of his nurse this is a magnificent performance (I weep now at its recall). If Mr. Cranham wants to play Lear this is his calling card.

Support for this tour de force is everywhere evident: in the patient understanding of his daughter (Lia Williams) and the pin accurate ensemble to the fractured music and lighting. If a set can be said to be stark and clever, Miriam Buether’s has achieved it. Director, James Macdonald, has cleverly navigated his way through the internal landscape with a sensitive and measured step.

The Ustinov continues to produce theatre, which by any standard is of the highest order and in this gem of a play has dealt a full hand of relevant, entertaining and moving. ★★★★★ Graham Wyles 21/10/14

Photos by Simon Annand