King Lear is, along with Hamlet, a sort of gauge of an actor’s skill. They are the parts by which an actor will move into the theatrical firmament or leave audiences disappointed. Hamlet is the part that every rising young actor worth his salt must play, Lear every older one. The problem with Lear is that it is traditionally seen as an old man’s part – all flowing robes and long, grey beard and hair. But there are lots of older actors who fear the part merely for its physical demands. However, there is no need for all the accoutrements of age – a fifty or sixty year-old man could easily have three grown up daughters and, as we all know, sixty is the new forty. So, Lear could, and perhaps should, be a part for an actor in his prime, not in his dotage. David Haig in the new Theatre Royal Bath production of King Lear goes a long way to demonstrate this.

King Lear is, along with Hamlet, a sort of gauge of an actor’s skill. They are the parts by which an actor will move into the theatrical firmament or leave audiences disappointed. Hamlet is the part that every rising young actor worth his salt must play, Lear every older one. The problem with Lear is that it is traditionally seen as an old man’s part – all flowing robes and long, grey beard and hair. But there are lots of older actors who fear the part merely for its physical demands. However, there is no need for all the accoutrements of age – a fifty or sixty year-old man could easily have three grown up daughters and, as we all know, sixty is the new forty. So, Lear could, and perhaps should, be a part for an actor in his prime, not in his dotage. David Haig in the new Theatre Royal Bath production of King Lear goes a long way to demonstrate this.

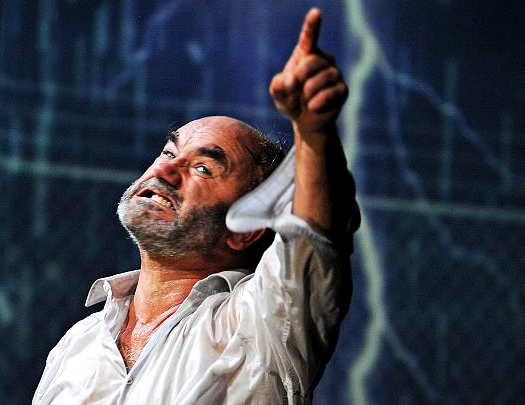

King Lear has become a bit of a cliché over the years. Yes, he has to have a beard because it’s in the script but nowhere does it say he has to look like Professor Dumbledore. So David Haig’s neatly trimmed whiskers made a nice change, as did his being fit and slim. Haig is a young, energetic Lear. He is 57 and plays 57 unlike recent portrayals – Derek Jacobi 71, Ian McKellan 68 and a bit longer ago, Olivier at 77. Michael Gambon was only forty-four when he took on the mantel, but played it much older.

The problem is that there are so many benchmarks already set. Everybody has seen someone play Lear and everyone has their favourite. And it seems to be done every couple of years by one of the major companies, so comparisons are unavoidable. It takes courage from both actor and director to set themselves up in the coconut shy of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy. To be successful you need to provide an outstandingly original production or a central performance that is a tour de force. Preferably both.

Lucy Bailey’s production of King Lear at the Theatre Royal is outstandingly original and David Haig as the tragic King is a tour de force. Forget the long grey beards and swirling cloaks, this is all the smart Saville Row suits, polished shoes and Brylcreemed hair of 1960s East End gangsters.

The first act was really quite scary. There was a real tension and a sense of menace which, being in modern dress we could more easily relate to. The sixties Mile End Road milieu was very effective and the gangster-type Lear was certainly in his element down the pub with his obsequious ducal henchmen. Everything was going fine until a silly, family party-type game got out of hand, as they often do, and that bloody Cordelia spoiled everything by not sycophantically gushing her love for her dear old dad. Well, she got what was coming to her, or rather didn’t, right enough.

Aislin McGuckin and Fiona Glascott were excellent as the brash Christine Keeler/Mandy Rice-Davies Goneril and Regan with their leopard skin coats, high heels and Friday night whooping while Fiona Button as a Hayley Mills Cordelia brought a little sobriety to the family. I liked Paul Shelley’s Earl of Gloucester. He had that simple, unquestionable, quiet loyalty about him. He was like a friendly, easy-going neighbour who is always happy to pop round with his screwdriver and help you put up a shelf or mend the wonky leg of your throne. But even he had troublesome children.

But the evening, of course, belonged to David Haig. He went from a smooth operator who lost his cool to tormented, thrashing-around-on-the-heath lunatic equally convincingly. However, his rantings at times came perilously close, like Gloucester on the cliffs of Dover, to going over the top. Haig, as we have seen in many previous performances, certainly does hysterical.

But it was in the final act when he had finally comes to terms with his situation and had become more introverted and philosophical that Haig really began to tug at the heart-strings. His pitiful, grateful acceptance that he would be finally and permanently re-united with his beloved Cordelia, albeit in a prison cell, was beautifully and touchingly done but when even that was cruelly taken from him, it was heart breaking – literally in his case

Visually most of the settings were achieved by projections on gauze. Some were more successful than others. The design by veteran, award-winning William Dudley was, ironically, at its best when the vast stage was completely and utterly bare. The two most breathtaking moments came when Cordelia re-appeared, first very much alive and then very much dead, back-lit through enormous double-doors on the rear wall.

By the end of the play all reference to the be-suited gangsters had gone and for the battle scenes everyone had became a bovver boy with Doc Martins, turned-up jeans and braces. Still very East End, but more Berkoff than Krays. I think it would have been more frightening and menacing if they had stayed smart – a man in a suit and shiny shoes wielding a machete is much scarier than a posturing hooligan.

King Lear is arguably Shakespeare’s most moral play dealing with themes of domestic frictions, sibling rivalry and greed with which we are all very familiar, at least we are down our way. In spite of being part of what appears a close-knit group and having our kith and kin around us, ultimately we are all alone. As Hamlet, Shakespeare’s other great troubled hero beset with family problems says, they can be more than kin but less than kind. Families eh, who’d have ‘em? Michael Hasted ★★★★★ August 2013

Photo by Nobby Clark