Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

William Shakespeare, As You Like It,

It took losing a front tooth to convince playwright and actor Trevor T. Smith that he could deliver a monologue about dementia. His missing central incisor certainly aided his depiction of a man crumbling, both outside and in.

During the Q&A that followed tonight’s performance at the Ustinov in Bath he was asked just how was it he had managed to glean the experiences of someone with a failing memory. He had, he said, just looked into himself and imagined a personal journey to oblivion in order to construct the play. Most gratifying to him had been the very positive response he had had from the British Medical Journal for the piece, that it in many ways spoke more than the textbooks to students of the condition. Three sell-out shows at the Edinburgh Festival have followed, and Smith has also been nominated for Best Male Performance in the Off West End Theatre Awards.

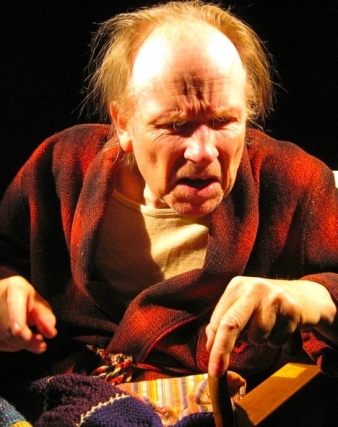

As we take our seats at the Ustinov, we find ourselves facing our dementia patient already sitting centre stage in his dressing gown, right hand shaking, tongue sometimes lolling, mouth uttering incomprehensible sounds. This is a look many of us have seen in hospitals and care homes. It’s not a happy sight. Those in death’s anteroom provide disquiet for many, if not only for being the proof positive of the end of human life. But do we stop thinking of these people as rounded human beings because their functions are shutting down and they don’t look too good? Smith is here to challenge our assumptions.

We are introduced to the psychology of surviving life in a care home. Smith talks of tricks – avoiding using names, staying quiet – if you don’t make ‘mistakes’ no one will know you have a problem. Don’t leave your chair; to do so would invite any number of disasters. Don’t swallow your pills, think of the side effects – it’s a constant cat and mouse end game with the ‘Bluecoats’ and the social workers.

For someone with dementia sitting doing almost nothing for hours has many downsides, but most graphic of all I thought was Smith’s worrying description of going down into a sea of hate from which he found it difficult to resurface from. In one poignant moment he recalls walking to the end of a pier as a child and seeing only an empty sea at the end of it, a fitting metaphor for his coming to the end of his life with nothing to focus on, no redemptive inner conversation, just a loneliness made worse with a white noise silence of the mind.

Smith uses the play to make wider points. “There is a lot of dementia about,” he says, “We are forgetting to care for one another in an everyday common sense sort of way.” Delivered by the man who no longer recognises his own family, this makes for powerful health politicking.

Smith’s convincing narrative makes us weep, sometimes ironically laugh at this uncomfortable yet for many inevitable seventh stage in the life of man. By putting the condition centre stage we are all helped to look at it in the teeth. ★★★★☆ Simon Bishop 25/01/15