It is late one evening in 1904. You are in your club; an oak panelled affair in whose fading light you can still manage to pick out details on the book-lined walls. The third brandy and your comfortable wing chair conspire – with the last remnants of a once cheerful fire – to do their work. The porter comes in to tell you that because of the January fog your Hackney carriage will be some time yet. Resigned to a tedious wait you sink further into your chair at which juncture one of the longer standing members slips into the room. A large man, he is surprisingly light on his feet and it is not until he has sat, uninvited, in the chair adjacent to yours that you are aware of his presence. The firelight and the candle placed on the side-table stood between the chairs allows you to make out his features, which, because of the angle of his chair, are presented to you in partial profile.

There is a certain nobility in the high, generous forehead and the light reflected in his spectacles appears to give a spirited twinkle to his eyes. The club’s excellent cellar encourages a certain easing of the usual restraints of propriety and you become aware, as you gaze inquisitively at the newcomer, that he appears to exhibit a certain agitation. It quickly becomes apparent that, like the Ancient Mariner, he has something he wishes to get off his chest and that you are the chosen audience for his unburdening. Too tired to assume the role of interlocutor you smile benignly as one pleased to accept, without demur, the petition of a visiting ambassador.

Speaking in a voice of distinctive timbre, like that of a bowl of partially rehydrated prunes, and notwithstanding the gravity of his story he narrates with an ebullience punctuated with moments of dark reflection and what you take to be shrieks of terror as he takes on the character of the poor souls which form the subject of his discourse.

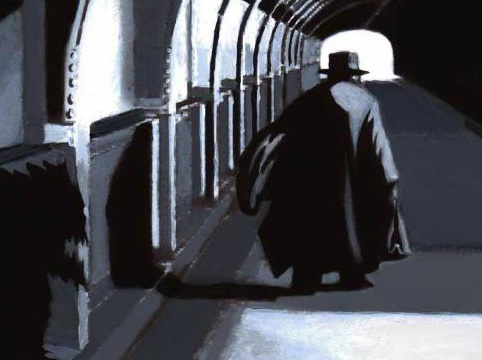

At first you are confused by a kind of mist which descends as you try to make out the various personages referred to in his tale, but as he proceeds you become aware of the malignant agency of one Doctor Karswell, otherwise known as the Abbot of Lufford; of some kind of curse involving an ancient runic script; of mysterious handbills and encounters in the library of the British Museum. The climax of his story relates a desperate, clandestine train journey the outcome of which was no less than the averting, from the unspeakable powers of the occult, some unnamed terror, which threatened a certain acquaintance of his named Dunning, from whom the details of the story were related.

Not content with having thus cast a mephitic gloom over your evening and chilled you to the bone, he further regales you with supernatural terrors, his long, sensitive fingers grasping and stabbing at the air as he relates a ’squalid act of sacrifice’ and other offences against God involving the incumbent of the Residence of Whitminster and a member of the aristocracy. Thus unburdened he rises and with a previously unnoticed humility, takes his leave. Collecting yourself you summon the porter. ‘Who was that gentleman?’ ‘Mr Lloyd Parry you mean, sir?’ ‘Singular fellow,’ you remark. ‘Is he often in the club?’ ‘Oh yes, sir. Many’s the night he’s drained the blood from the faces of members, sir, if you’ll excuse the expression.’ ‘Indeed, I’ve just had the treatment myself. Two gems and if I’m not mistaken, told by a talesman of the first water.’

You gather your thoughts and make your way out into the night, which you are pleased to find is clear and bustling. ★★★★☆ Graham Wyles 27/04/15