Orwell’s novel of existential angst (subsequently given the appearance of alarming prescience by events in the Cold War) set in a dystopian future, is well established as a classic of the genre. The mark of its status within the culture is that even those unfamiliar with the novel will likely have heard of Big Brother and Room 101 and thoughtcrime.

The story is an ironic take on a post war Britain which has supposedly been subsumed into the super-state of Oceania, that is ruled by the invisible, omnipresent being known as Big Brother and who is not known directly, but only through his iconic image. It is a dark vision in which ‘thought crime’ is relentlessly policed and punished.

There are those who would say the possibilities for a malign state to control the thoughts of the population are greater today than in 1948 when the book was written and indeed in 1984 when it is set. The idea of an invisible being, able to read one’s thoughts and demanding absolute submission currently flourishes in parts of the Middle East whilst a state with the capacity to collect information of the most sensitive sort on all its citizens is a very real possibility, as revelations by Messrs. Snowden and Assange et. al. have testified.

We might suppose that bringing the story up to date is consequently the matter of a mere flick of the pen. The adapters, Duncan Macmillan and Robert Icke, have performed the trick by a process of clever theatrical disorientation, which only begins to dawn on us, the audience, as the play progresses. When, early in the play, a bemused Winston declares, ‘I don’t know what’s happening’, as he is levered out of his own, contemporary, reality into one of repetitive confusion, I have to admit of having had an uneasy feeling that that was going to be my fate for the next hundred, uninterrupted minutes. Happily the mist soon cleared as temporal ambiguity emerged as the name of the game. The setting is now or some future ‘now’, we were being invited to suppose by this clever device.

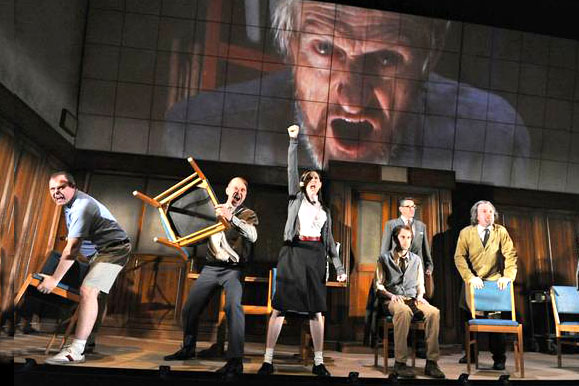

Sex and its cultivated cousin, love, emerge as the human antidote to all the mind control. Janine Harouni, as Julia, is the embodiment of a still beating humanity. She gives a performance of well-defined clarity as she changes from mindless automata to warm lover and rebel. Tim Dutton, as the cool party apparatchik responsible for enforcing conformity to and love for Big Brother, makes a chillingly plausible, if a little suspicious, O’Brien. Matthew Spencer brings a kind of universal ordinariness to Winston Smith, the thought criminal who defies the party by keeping a personal diary by which he maintains his psychological independence. it is the potential for nobility of spirit which abides in all of us, however humble, which ultimately stands as a check against the enormities of totalitarianism.

Clever staging and astute adapting make this rightfully unsettling production a worthy torchbearer for the vigil against despotism and could do with reviving at regular intervals. ★★★★☆ Graham Wyles 30/09/15