26 – 28 April

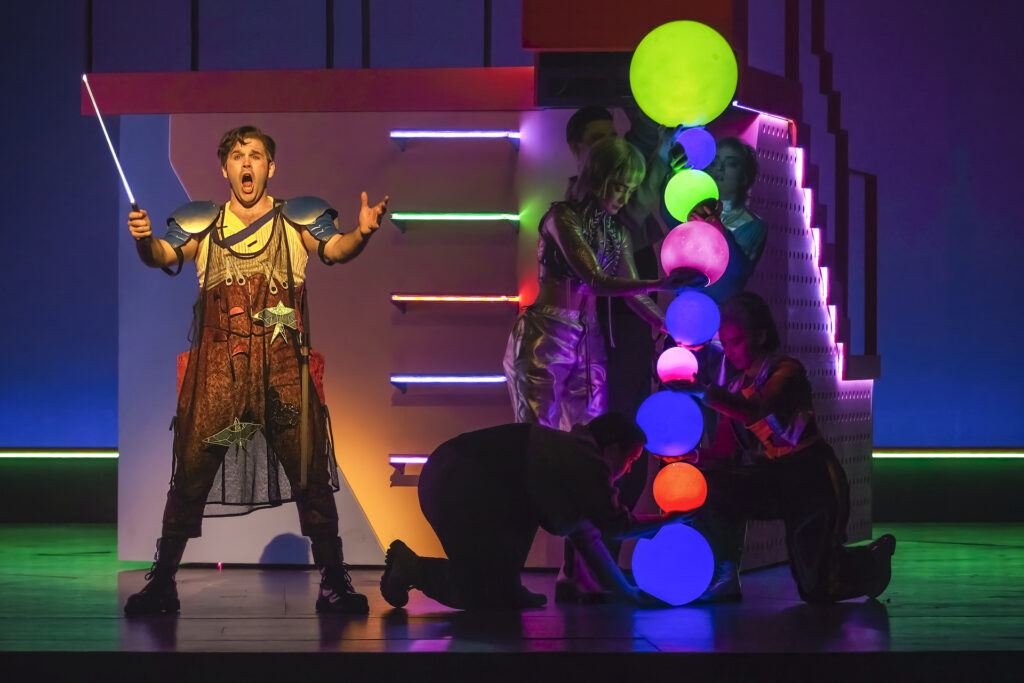

There are many reasons why a director might choose to depart from the original text of The Magic Flute. We are compelled to view this eighteenth century opera/pantomime through twenty-first century eyes, and there is no doubt that some of it jars with contemporary sensibilities. Director Daisy Evans has written of the ‘undertones of racism, misogyny and discrimination’ in Schikaneder’s libretto. Therefore, it is entirely reasonable that she has dropped the references to Moorish slaves, and scrapped the elements relating to freemasonry. Inevitably, she has also made significant adjustments to its depiction of gender roles. Fair enough. But she has gone much further, altering key relationships, and redirecting the moral compass of the fable. Such changes, if they are to be successful, require coherence and a lightness of touch. Unfortunately, those qualities are sadly lacking in this muddled, heavy-handed production, where even Tamino’s magic flute has been replaced by a kind of skinny light sabre.

A lack of clarity is evident right from the start, for the overture is accompanied by an impenetrable prologue involving dancers wielding illuminated balloons and neon lights. It is pretty to look at, but unless one has read the programme notes the meaning of it all is hard to discern, and trying to puzzle it out detracts from listening to the music. Appreciation of the prettiness of the balloons and lights quickly evaporates as the opera proper gets underway, for they are greatly overused throughout, and become tedious, as do the many puppet birds flapping away on long wands. Characters are seldom left alone, but are constantly surrounded by fussy stage business, and there are times when the glory of the great arias is lost amid all the extraneous goings-on.

Loren Elstein’s brightly coloured set features two large geometric blocks with stairs and platforms, one representing Sarastro’s world of daylight, and the other is the Queen of the Night’s realm of darkness. As the story progresses the blocks shift and rotate. These movements sometimes appear random, and there are times when it is not at all clear which of the two realms we are in. The generally unattractive costumes are a strange mix of Star Wars combat gear and Handmaid’s Tale religious vestments. Less attractive still is the dialogue, which is often jarringly banal, featuring such gems as ‘Wow, that’s awesome’ and ‘I miss my Mum’.

In this version Sarastro and the Queen of the Night are Pamina’s separated parents who have had a bust-up over her education. He espouses the supposed masculine qualities of logic and empirical reasoning, while she promotes the feminine virtues of intuition and emotional intelligence. This Queen of the Night is no longer the allegorical embodiment of superstitious ignorance, and Sarastro no longer represents the advancements of The Enlightenment. Instead, she is a well-intentioned mum who happens to see the world differently from her equally well-intentioned husband. The universal conflict of good versus evil has been reduced to the banal level of a domestic quarrel, where each party’s ‘truth’ is valid. These warring parents achieve a cosy reconciliation in the end, which is totally at odds with what Mozart’s music conveys. Mixed messages abound, and there are uneasy shifts in mood. The Queen of the Night’s great aria features a flashing circle of lights – undeniably spectacular but perhaps more appropriate to a Beyoncé concert.

Enough of the negatives. The singing is splendid throughout, and last night conductor Teresa Riveiro Böhm’s sprightly direction drew wonderful sounds from the WNO orchestra. Mozart’s music remains magnificent, but elsewhere there is disappointment. No flute, and very little magic.

★★☆☆☆ Mike Whitton, 27 April, 2023