27 April

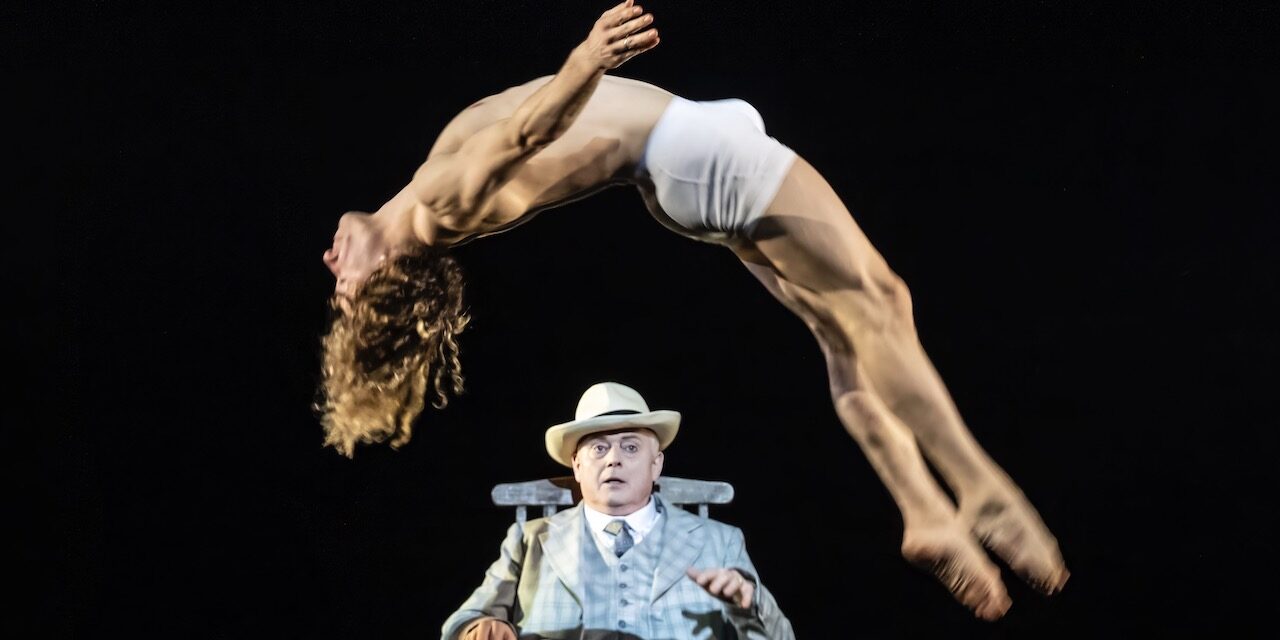

One theme that runs through Benjamin Britten’s Death In Venice, as in Thomas Mann’s original novella, is risk-taking in pursuit of beauty. The central character is the deeply conservative and sternly self-disciplined writer Gustav von Aschenbach, who decides to take a break in Venice in the hope that a change of air will cure his writer’s block. There he allows himself to become obsessed by the beauty of Tadzio, a young dancer, and though he knows an epidemic of cholera threatens, he stays on in Venice so he can continue to catch glimpses of the boy. In consequence he risks his health and, perhaps more importantly, he risks losing his highly moral sense of self. In this extraordinary production of Death In Venice, a collaboration between Welsh National Opera and NoFit State circus, the idea that the pursuit of beauty can be dangerous takes on a striking three-dimensional form, because director Olivia Fuchs has re-imagined Tadzio and his family as circus acrobats, whose gravity-defying feats combine aesthetic appeal with a sense that at any moment a slip could lead to disaster.

In a production where the eye is frequently drawn to spectacular happenings aloft, it is a tribute to the strength of tenor Mark Le Brocq’s performance as Aschenbach that he remains the most important figure on the stage. Antony César as Tadzio displays astonishing physical skills, as do all the other circus artists, but all the psychological and moral complexities of this opera rest with Aschenbach, and Le Brocq delineates them with every vivid gesture and change in vocal line. Aschenbach can be seen as merely pathetic – there is no fool like an old fool – or he can be condemned outright, but in Le Brocq’s precisely judged performance it is his tortured inner life that commands attention. ‘There is a dark side to perfection – I like that’ he comments, and that mordant self-awareness makes him more fascinating than repugnant. He knows that his pursuit of beauty is likely to be fatal.

There are considerable strengths across the entire cast, but countertenor Alexander Chance is especially memorable as Voice of Apollo, his glittering golden suit contrasting with the scarlet outfit of Roderick Williams’ Dionysius. Williams displays chameleon virtuosity in several contrasting roles, including the gloomy Charon-like ferryman who takes Aschenbach to the Lido, and the smooth-talking barber who deludes him into thinking that an absurd toupée will restore him to youthfulness.

The bright costumes of Apollo and Dionysius, figments of Aschenbach’s dream of the struggle between the beauty of art and the temptations of passion, offer the only splashes of vivid colour in a production that otherwise uses a monochrome palette to great effect. Aschenbach’s fellow hotel guests are all dressed in white, while the locals are in black or grey.

Sam Sharples’ video projections on the rear wall are also monochrome, often featuring hazy distant views of Venice across a great grey expanse of water. This creates an uneasy, somewhat oppressive mood as the threat of cholera looms, relieved by moments of great beauty, as when white-clad figures descend around the sleeping Aschenbach, like a visitation from angels.

It might be thought that a production that is so visually astonishing might fall into the trap of neglecting the aural experience, the music, and certainly there are moments when one’s attention is drawn entirely to the twirling figures of the acrobats. But Britten’s demanding, gamelan-influenced score, with its innovative use of vibraphone and exotic percussion, is delivered magnificently by the WNO orchestra and chorus, and the soloists all bring great musicality and vivid characterisation to their roles. Under Conductor Leo Hussain the music is not, in my judgment, overshadowed one bit. Last night’s performance was interrupted in the second half by a most unwelcome front of house disturbance that brought matters to a temporary but quite lengthy halt. It is a tribute to all the cast and musicians that when the performance resumed the audience became swiftly absorbed again by the sights and sounds of this morally ambiguous and deeply fascinating opera.

★★★★★ Mike Whitton, 28 April 2024