16 August – 8 October

Of all Shakespeare’s so called ‘problem plays’, All’s Well That Ends Well is the most problematic. The young lovers are hard to like, the humour is cruel, and the plot both contrived and absurd, with its combination of fairy tale romance and crude cynicism. Yet this startlingly innovative production, directed by Blanche McIntyre, sheds new light on a play that has often been avoided by theatre companies, hurling it into the 21st century, underlining its dark psychology and creating a fable for our times.

A flexible dome structure serves as both palace and army camp, working equally well as a wide backdrop to the shifting, flashing images of a computer screen. In front of this, the action is played out on a bare blue stage, itself suggestive of a virtual reality, underpinned by an eerie sound world of amplified strings and percussion. Happily, this juxtaposition of old and new feels wholly unforced.

One of the many difficulties of All’s Well is the often tortuous language, but the production confronts this head on with powerful, well-articulated performances from all the principals so that there is never any sense of dislocation between the convoluted Elizabethan rhetoric and the modern world on stage. In fact, the feckless young men addicted to indoor war games and social media, are credible versions of the layabout gentry in the French court, ‘sick for breathing and exploit.’

The cast is superb, each of the principals demonstrating their character’s psychological transformation. Rosie Sheehy as Helena enters in school uniform, a gauche, pink- eyed teenager, doting on the handsome noble Bertram who barely looks at her and is understandably horrified when told he must marry her. She develops into a young pregnant woman of such poise and confidence that we are persuaded that he might even come to love her despite his initial revulsion. Most critics have found him impossible to like, but Benjamin Westerby breathes life into him as a normal young man, prey to powerful social pressures and sexual urges. If he lacks moral sense, it is easy to see why in a world where honour is bound up with image. His antagonism to the King’s edict is perfectly plausible, though he too is transformed by the end.

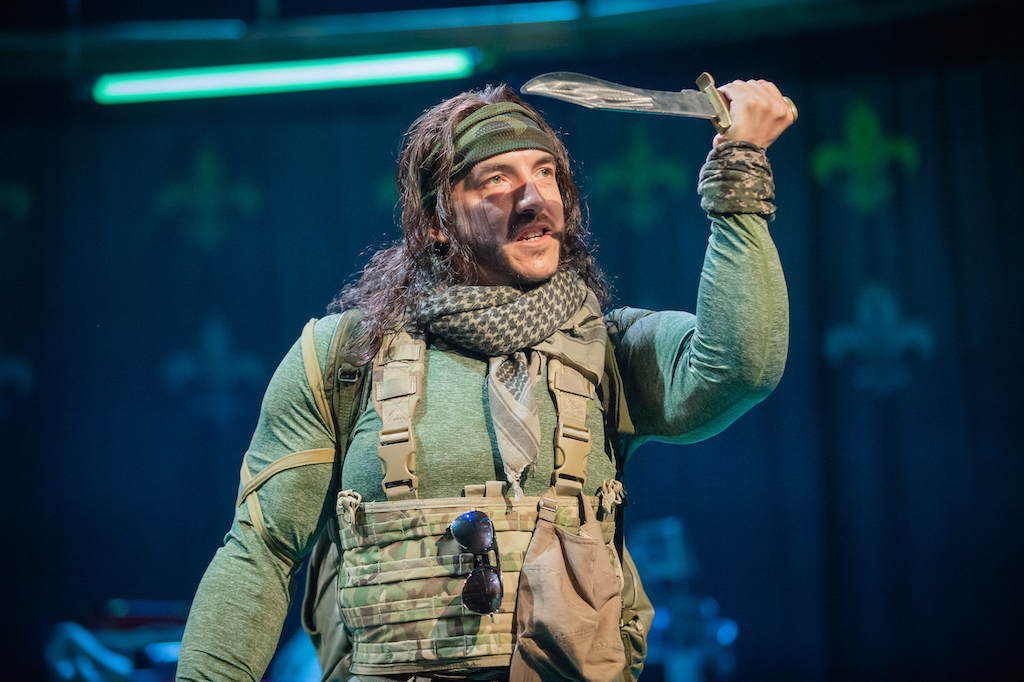

Another great revelation of this production comes through Jamie Wilkes’ astonishing portrayal of Parolles. He rolls in, Rambo style, trussed in combat gear, posing for selfies, mocking those around him, instantly recognisable in a role as pertinent and pervasive now as when the play was written. His humiliation is both comic and horrifying, leaving a nasty taste as he is hooded and dragged around the stage on a rope. Even after his release there is no escape, as he remains the butt of internet trolls. His final decision to be true to himself, not some fake version of himself, has a powerful resonance in the era of the curated image.

The older generation is equally convincing. The countess, one of the few warm-hearted characters, is played with stately gravity by Claire Benedict. Bruce Alexander’s King of France has a powerful egotistic authority. And Simon Coates brings brilliant comic timing to the smaller role of Lafew.

All’s Well That Ends Well is an unsettling play. Helena and Betram have both grown in emotional and psychological stature during these strange events, but the audience is left more troubled than moved by their story. Is all well? As they face each on an empty stage after the King’s ambiguous closing speech, it is a question with no clear answer.

★★★★☆ Ros Carne, 24th August 2022

Photo credit: Ikin Yum